Brought to you by the Land Acknowledgement subcommittee of the Faculty Senate and the Office for Social Justice and Diversity.

How much do you know about contemporary Native American societies, cultures and their histories? What steps can we take to support the struggles of Native Americans for justice? Listen to and watch revolutionary artists, join discussions, discover critical truths and become an empowered ally. You’re invited to join us in a 5-day Challenge from Monday, November 16 – Friday, November 20.

Today we are in the midst of a profound global revolution where first peoples everywhere are rising up to challenge past and current oppression and imagine radically different postcolonial futures. The telling of stories, the recovering of histories, languages and cultures — and the shaping of new ways of being alive are being innovated by Indigenous artists today across Turtle Island (North America) in the most astonishing, profound and beautiful ways.

The creative practices of contemporary Indigenous cultures offer all of us radical alternatives outside of problematic western narratives. Let’s listen, watch, learn, transform and join them in resisting, changing and welcoming new futures:

A short playlist for Indigenous futurism:

- Tribe Called Red

- Tanya Tagaq

- Stand Up

- DJ Shub

- Calling all dancers

- Lyla June

- Snotty Nosed Rez Kids

- Kelly Fraser

Make your own Indigenous playlist and share with us and your friends

Modern colonial ideas of art have been problematic for all of us — separating experimental practices of ritual, toolmaking, spirituality, and music from our lives and putting them in arbitrary categories of arts, crafts, tradition, culture, history. Lets decolonize our minds, institutions and practices and see how contemporary Indigenous cultures and artists are alive and pushing boundaries to make new futures possible. Here is a very short list of things to watch, listen to, and see:

- Rulan Tangen (dancer and choreographer ) TEDX talk on the revolutionary power of dance as worldmaking: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OOOVohQUrzg

- Alan Michelson (Mohawk installation artist based in NYC): https://www.alanmichelson.com/

- Faux Reel podcast (Indigenous filmmakers): https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/faux-reel-podcast/id1498621703

- Isuma Inuit Film: http://www.isuma.tv/isuma

To do and to ponder:

- Amplify the voices of Indigenous artists: follow and share their work on social media — with us and your friends

- How would we decolonize our institutions, practices and mindsets in collaboration with Indigenous peoples? Start a discussion

- How does Indigenous art help us imagine and design a better and more just future?

- What can contemporary Indigenous art tell us about Native experiences?

- Must traditional Native expressions exist outside and apart from the contemporary art world? If not, how do they inform contemporary artistic practice? How do Indigenous artists challenge art world paradigms?

- What does an Indigenous artist look and sound like?

- Is art a colonial concept?

- Tell us about Indigenous artists you love who are not featured here

TONIGHT November 16, 2020! Join the Montclair State University watch party for US Poet Laureate Joy Harjo’s webinar! RSVP here: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSflVSbjreonOjB5hlBwqviK1gbFwCmEfoQ4UXLPnazj_zm86w/viewform

Additional resources:

Indigenous nations are the oldest sovereign nations in North America. Their sovereignty – in other words, their authority to self-govern – stems from the fact that their nationhood predates the United States and Canada. Among these diverse Indigenous nations there is no single vision of what self-government looks like. Each nation incorporates their own particular traditions of law and governance. Yet they all continue to struggle not just to exercise this right to self-government, but also to have their sovereignty recognized by surrounding states, provinces, and national governments. This includes many Native nations’ ongoing fight to have a voice in decisions that impact their sacred cultural sites and affect the health and wellbeing of their communities.

This struggle for recognition has international dimensions. The territories of the Six Nations Iroquois or Haudenosaunee traverse the present-day U.S.-Canadian border in the northeast. World Lacrosse recently denied their national team, the Iroquois Nationals, a place in the World Games because they do not recognize the Iroquois’ sovereign independence from the United States and Canada.

Ireland Lacrosse Bows Out Of 2022 World Games So Iroquois Nationals Can Play (2:00)

NPR, Morning Edition, 1 October 2020

This fight for recognition also takes place locally across North America. The Ramapough Lenape, Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape, and Powhatan Renape nations successfully petitioned New Jersey for state recognition in the 1980s. When the Christie administration rescinded that recognition, the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape nation successfully fought to have it reinstated. The Ramapough Lenape nation continues to fight to protect their territories from further environmental degradation.

Rev. Dr. John Norwood of the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape (9:09)

An interview from 2017 for “Building Greater Understanding about Native Americans”

The Ramapoughs vs. the World (5-minute read) The New York Times, 14 April 2017

Many other nations, such as the Ohlones in California, continue to fight for recognition. While in some ways specific to their particular history, their story also resonates with the struggles of other nations whose territories now include urban areas.

Beyond Recognition (24:28)

In the United States, nations who made treaties with the U.S. have fought legal battles to have the federal government honor those treaties. Others without treaties, such as the Mashpee Wampanoags of Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard, have successfully undergone the arduous process of gaining federal recognition. Together, these nations make up the 563 nations who have a “nation to nation” relationship with the federal government. But as the Mashpee Wampanoags reveal, the protection offered by this recognition can still be precarious.

The Breakdown: Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe Land in Trust (12:07)

MashpeeTV, February 2020

What can I do next?

- Sign a petition to #standwithMashpee

- Support HR 312 by writing to your congressional representatives

- Follow Splitrock Sweetwater Prayer Camp @splitrockprayercamp

Additional Resources:

- What is sovereignty?

- Why are treaties still important?

- NPR, Why Treaties Matter (5:20)

- Smithsonian NMAI, Nation to Nation (4:44)

- What is a federally recognized tribe?

- What is an “unrecognized” tribe?

- On the fight for recognition in New Jersey, see also:

- On Littlefield v Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe (2020), see also:

Environmental justice (EJ) is the right of every citizen regardless of age, race and gender, social class or any other factor, to adequate protection from environmental hazards, such as health impacts from air pollution, water and land contamination. It will only be achieved if all people have equal protection from environmental and health hazards and equal access to decision making processes that impact communities. Seeking environmental justice for Native American communities draws together issues of sovereignty and traditional connections to homelands, while engaging Indigenous people in an effort to address environmental problems in their communities.

Reimagining a future that protects Indigenous people from environmental hazards involves redirecting past efforts to address environmental injustice. The Indigenous Environmental Network suggests: “We must recognize the way governmental infrastructure, jobs, the environment, and our communities are being negatively impacted by not only the climate crisis and demise of capitalism, but also the way these impacts are exacerbated by a global pandemic with Covid-19. It is our stance that the problems created and perpetuated by colonization and capitalism cannot find solutions in those same frames. This is why it is crucial our Indigenous communities and nations recognize our place in this conversation.” (See the Indigenous Environmental Network’s “A People’s Orientation to a Regenerative Economy”).

How Indigenous People are Involved in Environmental Justice:

- Watch this 10-minute TED talk by Tara Houska (Ojibwe) where she reflects on her personal experiences at the largest Indigenous-led environmental resistance movement in US history: the #NoDAPL movement at the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota (2016-2017).

- Read this article by Raymond Foxworth on the relationship between Indigenous communities and Environmental Justice and environmental resources.

- Dina Gilio-Whitaker (Coleville Confederate Tribes) is Policy Director at the Center for World Indigenous Studies. Check out her excellent article “What Environmental Justice Means in Indian Country.”

What can I do next?

#1: National EJ Issues:

- Visit the Indigenous Environmental Network to explore their current activities.

- Explore the Environmental Justice Atlas, which maps information on communities struggling with environmental inequity.

- To understand some of the health impacts environmental conditions have on Indigenous communities and the need for more research, see this article in Prevention Science or this one from Environmental Health Perspectives.

- Read this interview or podcast with author and Indigenous researcher, Dina Gilio-Whitaker about environmental, food, and climate justice.

#2: Local EJ Issues in New Jersey:

- Read about NJ’s environmental justice bill (S232, passed in 2020) here.

- To learn more about environmental justice in New Jersey, check out Mann V. Ford. This HBO documentary explores the class-action lawsuit filed by the Ramapough people against Ford Motor Company’s deadly contamination of traditional Ramapough lands in Ringwood, New Jersey. MSU students, faculty, and staff can view the full film online through the Harry A. Sprague Library website.

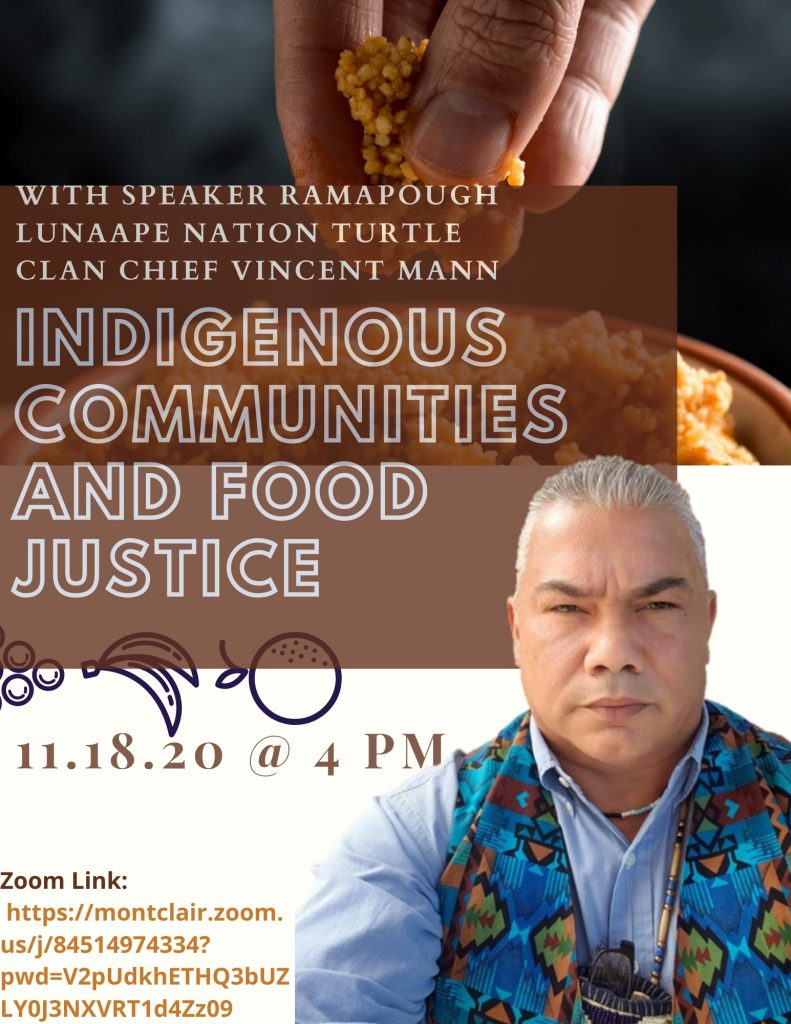

#3: MSU Virtual Panel Tonight 11/18 at 4 PM

- Join a virtual panel discussion entitled “Indigenous Communities & Food Justice” featuring Chief Vincent Mann (Turtle Clan Ramapough Lunaape, NJ). Hosted by MSU student Manar Alsaidi.

- Zoom link here. https://montclair.zoom.us/j/84514974334?pwd=V2pUdkhETHQ3bUZLY0J3NXVRT1d4Zz09

There are about 7,000 languages spoken today, with a small number (around 350) spoken by the vast majority of people — languages such as English, Mandarin, Spanish, Hindi, and Arabic. These “global” languages tend to obscure the rich linguistic diversity that exists throughout the world. What do you know, for instance, about Wampanoag, Maori, O’odham, Guaraní, or Hadza?

These languages, among many others, belong to vibrant communities of Native and Indigenous peoples around the world, who use them to create innovative artforms, literature, film, and song (check out this interview with filmmaker Prof. Jeff Palmer). In doing so, native speakers honor and sustain thousands of years’ worth of cultural knowledge and traditions. Other languages, meanwhile, are at risk of becoming dormant, and so native and indigenous linguists, teachers, and community leaders work hard to bring them into everyday use and train new generations of speakers. Revitalization efforts include documenting oral traditions through digital “Talking Dictionaries” (see Lenape examples from the NJ area here), establishing schools and immersive environments for learners, such as “language nests,” and much, much more. We can’t wait to hear what you learn about indigenous languages from today’s challenge!

Questions/Activities

A. What can you find out about the Indigenous languages spoken in New Jersey?

- Here are two places to start

B. Languages exist along a continuum of flourishing to endangered. Can you find some examples of Indigenous languages that have continued to gain new generations of daily-use speakers and those that are currently at risk of becoming dormant?

- Consider consulting the Ethnologue database at Sprague to find this information: https://www-ethnologue-com.ezproxy.montclair.edu/?ip_login_no_cache=%5D%A2-%E3CF%15q&cache=

C. What has happened to threaten the status of certain Indigenous languages over the years? And why?

- You may want to consult this article about the history of Indian Boarding Schools

D. What initiatives are currently underway to preserve and maintain the vibrancy of indigenous languages across North America?

- Take a look at the Talking Dictionary created by Lenape speakers of the Delaware Tribe: https://www.talk-lenape.org/

- Check out the work of the Living Tongues Institute for Endangered Languages: https://livingtongues.org/

- More than Words: Documenting the Paiute Language: https://www.lastwhispers.org/northern-paiute

What Can I Do Next?

- Donate to language revitalization projects

- Watch a movie or download music that’s in an indigenous language. Examples:

- Check out “One Day in the Life of Noah Piugattuk” (trailer: https://youtu.be/zsHJqSz5sdw)

- A Tribe Called RED: http://atribecalledred.com/

- Sign up for virtual Lunaape classes: https://elalliance.org/2020/10/classes-fieldwork-and-more-virtually/

Additional Resources:

- This 10-minute video, from Native Words, Native Warriors, an exhibit developed by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, features several Code Talker veterans: https://youtu.be/tna_cCLpBLw

- Pidgin: The Voice of Hawaii https://montclair.on.worldcat.org/oclc/921963260

- The Endangered Language Alliance works to maintain the languages of native speakers living in NYC: https://elalliance.org/

- Check out this collection of short videos focusing on native cultures and languages across the Great Lakes region: https://theways.org/index.html

- There are clear connections between the status of Indigenous languages and mental health within Indigenous communities. Here is just one example: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228465754_Aboriginal_language_knowledge_and_youth_suicide_Cognitive_Development_22_393-399

Resources compiled by Rashidah Manongdo and Prof. Elaine Gerber

The struggle of Native Americans to survive has come into sharp focus in 2020 as communities across North America have faced high rates of COVD-19. According to the CDC, Native Americans and Alaskan Natives are three times more likely to contract COVID than white Americans. The most well-documented story has been on the Navajo Reservation in southwestern United States. COVID rates there surpassed rates in any other state in the US, including the highest rates recorded in New York and New Jersey. Less is known about COVID rates in other tribes, but this is partly a result of problems in the way health statistics are collected. Doctors often misidentify the racial or ethnic heritage of their patients by marking an Indigenous person as Latinx or Hispanic. Other issues that surfaced with onslaught COVID in Indigenous communities derive from the generations of poverty, poor healthcare, and isolation that left Native people especially vulnerable to the disease. The evidence shows clearly that high rates of COVID are direct results of bad Indian policy and anti-Indian racism. Indigenous North American communities are in dire need of help.

We provide here several resources below that will give you more information and awareness of their struggle as well as ways you can help.

Why Are So Many Native Americans Dying From Coronavirus? (Video, 9:44)

This video shows that Navajo people are facing incredibly high rates of the Coronavirus. You will see how COVID-19 exacerbates existing problems such as lack of safe drinking water and food sources, the need to leave homes and the reservation to get resources, and a lack of available child care. The video also shows that some Navajo people are getting through the pandemic through a return to their cultural and spiritual roots.

‘Still killing us’: The federal government underfunded health care for Indigenous people for centuries. Now they’re dying of COVID-19 (USA Today, Oct 2020)

This article looks at the historical legacy of neglect of the Navajo Nation by the US Government. From a broken treaties to the nonpayment of promised funds to a shortage of hospitals, doctors and nurses, Navajo and other Indigenous communities were structurally unprepared for the pandemic. These issues are evidence of systemic racism and a long-term pattern of failed government action. To survive the Navajo have relied on their own cultural resilience, a habit developed over centuries of conflict with colonizing whites.

The CDC Doesn’t Know Enough About Coronavirus In Tribal Nations (NPR Sept 2020 ~14 minute listen)

This news story describes the ongoing fight against COVID-19 in Native American communities which have much higher rates of infection than non-Native communities. The point of the article is that Indigenous people also suffer from a lack of adequate understanding about their health and social life. As Jourdan Bennett-Begaye (Navajo), the deputy managing editor of Indian Country, states “the CDC doesn’t really know tribal communities and know the Indian health system and how it’s built and set up.” Without these data, documenting and treating the disease is hampered even further.

What can you do?

Educate yourself about how to do your part to not spread COVID-19.

Read COVID-19 Policy Brief: Disparities Among Native American Communities in the United States.

- This report by the Infectious Diseases Society of America documents data collected by the Indian Health Service (a division of the Dept of Health and Human Services). You will find several Calls to Action that you can demand the Federal government pursue.

Follow

- Social distance Pow Wow/#socialdistancepowwow

- #IamsewingfortheNavajoNation

Additional resources

On testing and contact tracing in Native communities

- https://www.npr.org/2020/04/24/842945050/navajo-nation-sees-high-rate-of-covid-19-and-contact-tracing-is-a-challenge (Clip from April 2020 (~3 mins):

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/challenge-covid-19-and-american-indian-health

On the history of viruses as part of colonial relations

On Native Women as Frontline workers

Perspective from the BBC

Fact Sheets:

- CDC: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0819-covid-19-impact-american-indian-alaska-native.html

- ScienceMag (profiling Abigail Echo-Hawk, a citizen of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma and director of the Urban Indian Health Institute): https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/09/covid-19-data-native-americans-national-disgrace-scientist-fighting-be-counted

History

- HIST 211 – Native American History

- HIST 342 – Frontiers and Borderlands of the Americas

- HIST 340 – History of Mexico

Religion

- REL 254 – Native American Religions

- REL 352 – Conquest & Resistance: Europeans in Native America (1500-1700)

- REL 382 – Indigenous Voices Today

Anthropology

- ANTH 120 – Native Americans

- ANTH 320 – Caribbean Archaeology

- ANTH 325 – North American Archaeology

Copy and paste the following link or click here to sign up for the challenge: https://montclair.us2.list-manage.com/subscribe?u=f77c5849e00cd33a4361e0e34&id=eb0b9460f7