This class is aZoo!

Course at Turtle Back Zoo gives students the opportunity to help keepers with research and animal conservation

Some students sit on the ground, others lean against posts or stand as they discuss primates with the professor, who crouches in front of the group, so as not to obstruct the view of the gibbons swinging on ropes behind her. One gibbon hangs from a vine, staring at the students and making faces as though they are the ones on exhibit. Another quietly grooms herself on a ledge, ignoring the rambunctiousness of the others. Welcome to class at the zoo, officially Primate Behavior and Ecology, and Methods in Primatology.

Offered for the first time this spring, the combined undergraduate and graduate course met all day every Thursday at the Essex County Turtle Back Zoo in West Orange. The six-credit course, which started in the bitter cold of January, took place outdoors no matter the weather. Through a partnership with the zoo, 18 graduate and undergraduate students mostly studied primates – gibbons, tamarins, galagos – but also conducted observational research on other species including sea lions, otters, wolves, manta rays, toco toucans, a cheetah, a snow leopard and a red panda.

“These students aren’t just learning how to be scientists, they are scientists in this class, and I couldn’t feel better about the future knowing it’s in their hands,” says Assistant Anthropology Professor Cortni Borgerson.

Borgerson says the students were laser focused on “securing a better world for primates through behavioral research and conservation” and never complained about being exposed to rain, sleet or snow. Instead, they shared tips on the best outdoor gear, long underwear and layering up for prolonged exposure.

Climate and temperatures aside, zoo class is fun. “The coolest part are the lectures in front of animals. This week it was the gibbons, last week it was in front of the penguins,” says Miranda Muniz, a graduate student in Sustainability Science. “It’s a unique classroom experience.”

Borgerson, a primatologist and conservationist who has been working to save endangered lemurs in Madagascar for years, wanted to offer the primatology class at the zoo because she wanted students to get to observe animals, rather than just look at slides of different species, so she wrote to Zoo Director Jilian Fazio with a proposal to teach her class at the zoo.

Fazio jumped at the proposal. Having taught a similar course while an adjunct professor at George Mason University at the Smithsonian National Zoo in Washington, D.C., she knew it would benefit the students and the zoo.

Fazio gave Borgerson a list of animal behavior research projects that the animal keepers identified for the students to work on. The students added some of their own, resulting in more than 40 areas of study. “They’ve designed their own research, and that really helps build their confidence,” Borgerson says. “And even though the work is hard, it’s fun.”

Throughout the course, students applied for grant funding, conducted research, and presented or published their findings – and helped the zoo collect data about the behaviors of its animals.

“It’s a phenomenal partnership,” says Fazio, a Cranford native who returned to New Jersey to lead the Turtle Back Zoo in December 2020. “I’m excited about having the next generation of conservationists on zoo grounds.”

The partnership with the zoo also allows students to perform a valuable community service. “The keepers have done a good job of making sure all the work goes back to contribute to the long-term conservation mission of the zoo,” says Borgerson.

Because Turtle Back does not have its own research department, the collaborative research by Montclair students is significant, says Fazio. “All of that information helps us to make decisions on how best to manage the animals.” In addition, some data can be shared with other zoos, which are connected through the 240-member Association of Zoos and Aquariums. “Most people don’t realize that all zoos and aquariums are connected and collaborate both on species we manage and conserve in the wild. We share data and learn from one another,” Fazio says.

On one of two visits to the class, the weather is chilly but not too cold; the students are dressed for rain that’s expected later. The day starts with a lecture and all of the students are engaged and focused, oblivious to zoo staff zipping by on golf carts, the beep-beep-beeping of a nearby earth mover working on a new exhibit – and even to visitors eager to see the white-cheeked gibbons’ exhibit.

After the lecture and discussion, students head to their respective exhibits to do three hours of research and observation of the animals, recording data right through lunch. They reconvene in the afternoon for a session on statistics and interpreting the data they’ve collected.

Gibbon Back to the Zoo

The gibbons – Sumo, 6, Knox, 5, and Mu, 4 – are energized, swinging from rope to rope playing what appears to be a game of tag. Suki, the 19-year-old mother gibbon, surveys her charges from atop a window ledge.

“It’s just beautiful getting to know them,” says Adriana LaVarco, one of four students studying the behavior of the white-cheeked gibbons, which are critically endangered. “Suki has a strict personality.” She especially enjoys napping, eating and being groomed by her biological son Sumo, and her two fosters, Knox and Mu.

LaVarco and fellow student Hannah Kutler explain they are collecting four types of data: continuous (timing an activity for as long as it lasts); interval (recording what the gibbons are doing every five minutes); spatial (noting the location where the activity takes place); and all occurrence (recording whenever a behavior occurs). The students want to understand which spaces within the enclosure the gibbons enjoy the most.

All of this information is gathered and recorded in Zoo Monitor, an app used by all zoos. It will be analyzed and distilled into statistics and shared with Turtle Back animal keepers at semester’s end.

LaVarco, a graduate student studying Biology with a concentration in Physiology, is researching whether white-cheeked gibbons have a sense of self – and self-recognition. Her proposal to place a mirror in the gibbon house was approved and she’ll study how the gibbons observe themselves in the mirror.

“We know that chimps and orangutans have a sense of self, but gibbons aren’t studied as much,” LaVarco says. “I want to see if they look at themselves or their body parts in the mirror. And to see if they notice anything different if we put a smudge on them.”

Joselyn Molina is studying how Suki interacts with the foster gibbons and whether it differs from her interactions with her biological son Sumo. Meanwhile, Kutler is observing how the fosters and biological offspring interact with mom Suki.

“They go all day long,” observes Molina, a senior Anthropology major who took the class because it sounded so different from anything she’d ever taken. “When else am I going to see primates in person for class?”

A freshman Anthropology major, Kutler wants to be a primatologist and hopes to someday study under Borgerson in Madagascar, where the professor is trying to save endangered lemurs by helping people farm insects as a protein source instead. This class has been inspiring for Kutler, who has applied for a research grant to return to work with the gibbons next fall.

“I have so much to learn,” Kutler says, adding that she has grown particularly fond of Knox. “He’s so sweet.”

Cat’s Best Friend

Up the hill from the gibbon house, Jasper Majeske, an Anthropology major, stands along the fence outside Nandi the cheetah’s habitat. If Nandi moves or walks along the fence, Majeske moves, recording his observations on his tablet. Majeski’s research focuses on how Nandi uses her new habitat in varying weather conditions and on how often and where she interacts with Bowie, a 3-year-old Labrador Retriever, who is her companion. As nearby signage explains: “In zoos, dogs are used as companions for cheetah cubs that do not have siblings to grow up with.” From the look of things, these two are besties. In fact, born just one week apart, the two have been together since they were cub and pup.

“They’re chill with each other,” says Majeske, keeping an eye on Nandi so he can record her behavior in three-minute intervals. “They nap together and groom one another.”

When the two are apart and Bowie returns, Nandi goes to the gate and starts purring, he says. “It’s really cute.”

A Howling Good Time

Miranda Muniz is studying the gray wolves, Fargo and Zander, two 10-year-old males. Completing her master’s in Sustainability Science, she is examining how the wolves use the space in their exhibit.

Muniz logs how much time the wolves rest, as well as all occurrences of barking, howling and grabbing things. “When ambulances go by, they howl,” Muniz says with a laugh. “The first time it happened, it was super cool. I texted everyone I know and sent a video.” Muniz explains that she’s on the lookout for stress behaviors but both Zander and Fargo are pretty relaxed.

Despite working solo, she finds the coursework gratifying. “It’s challenging to be very independent and be up here by myself, but my research is very rewarding, so hands on,” she says. “I get to learn by doing. This is not just a term paper I have to complete to get a grade; people are waiting for this information that we were brought on to research.”

Red Panda-monium!

Each week, Lexie Lawson, a graduate student studying ecology and conservation, sits in front of Jerry the red panda’s house, monitoring his behaviors to get a sense of his overall health. Soon he will be paired with a mate – a recommendation by the Association’s Species Survival Plan – and produce what zoo officials call “genetically valuable offspring,” or at least that’s the hope, as Jerry will be getting a new home and a “girlfriend” soon. It is like a dating service for animals, Fazio says.

On this day, sitting on the ground on a purple yoga mat under an umbrella to protect her laptop from the drizzle, Lawson logs Jerry’s every move as young children rush up to get a glimpse of him – excited by a real-life version of the animated panda in the Pixar movie Turning Red that opened in March.

“As challenging as this course is,” Lawson says it has real-life applications that are already serving her well. “I’ve written my first grant proposal, and I’ll be able to stay on and keep working on this research through the end of the year.”

Who Can? Toucan!

In the reptile room, students Kristina Ollo and Jaileen Murillo are observing the courtship behavior of toucans, when a 2-foot-long, orange-headed caiman lizard named C.L. – climbs onto and curls up on animal keeper Rachel Gentzler’s calves as she kneels to clean the pond in the glass enclosure. As lizards go, this one seems particularly friendly.

C.L. then climbs onto Gentzler’s back, to the delight of children visiting the zoo on a class trip. Despite the show C.L. is putting on, Ollo and Murillo keep their focus above the action – on the toucans – noting how the tropical birds’ behavior is affected by humans. Ollo is observing 3-year-old Coco, who wears a silver band around her leg, while Murillo keeps an eye on 2-year-old Julio, who sports a red band and was brought in as a potential mate for Coco.

Mating season begins soon, so the students are observing the birds’ spatial activity – how far from or close to each other they stay and if that behavior changes around humans.

“These birds haven’t mated before but they’re starting to court,” says Murillo, an Anthropology and Spanish major, explaining that in toucan land, “courting” looks like one bird nipping at the other’s beak.

Using a decibel meter, biology graduate student Ollo is recording noise levels when visitors enter the reptile house to determine how sounds might affect Coco’s and Julio’s courtship behavior.

She plans on writing her thesis on American kestrels, the smallest hawks found in North America. “I want to work with and research birds, so this class helped me figure out how to do that,” Ollo says, “It helped with the process of coming up with research questions, writing a grant, things I wouldn’t normally learn in any other class.”

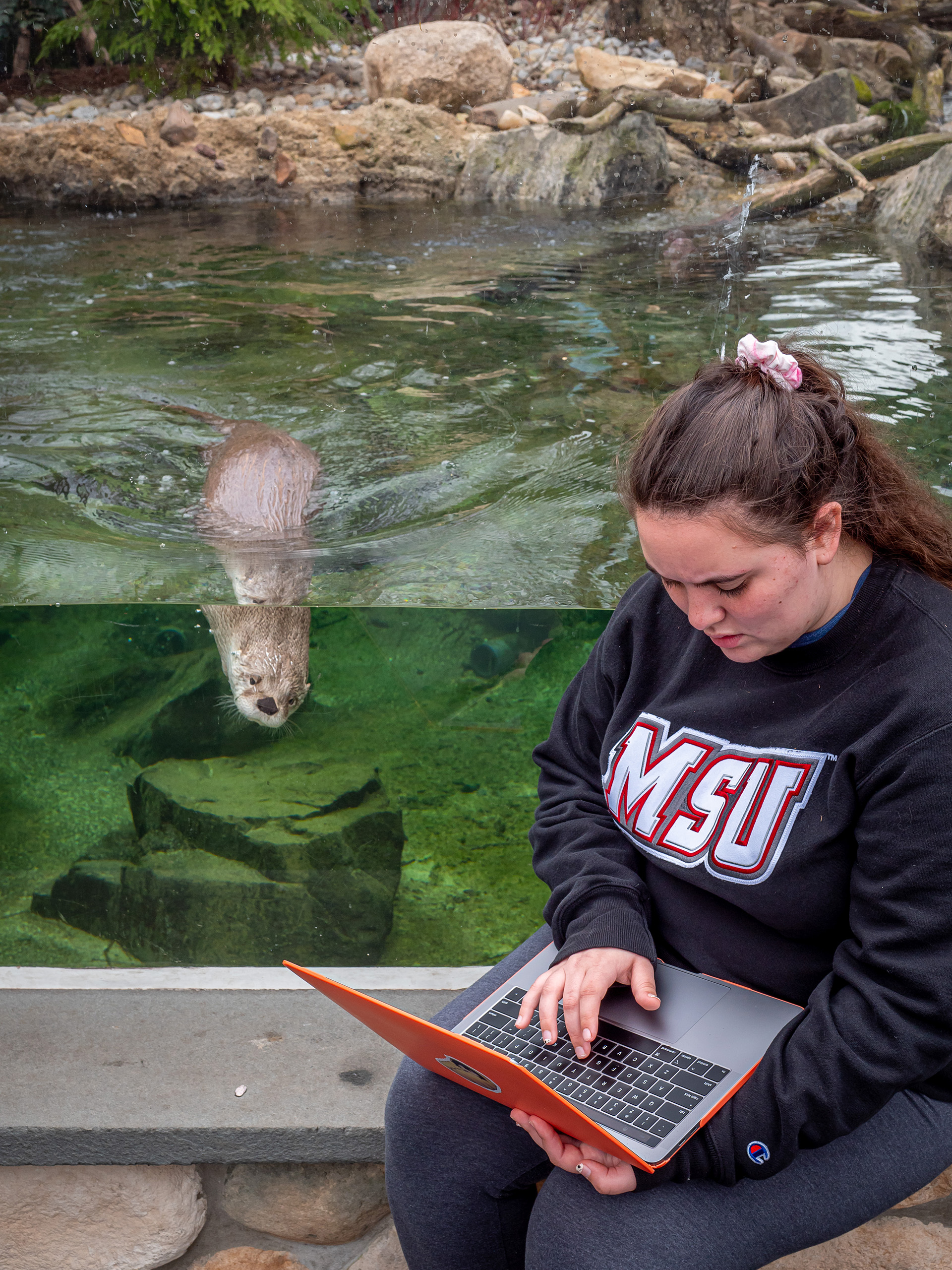

This, That and the Otters

Undergraduate students Vanessa Glaser and Diana Sisk-Gritz spend their days at one of the most popular attractions at the zoo: the otter habitat. The otters, Han and Shelby, are popular because they are playful and their glass enclosure lets them be seen both above and below the water. Plus, otters often put on a show.

Glaser, an Earth and Environmental Science major, and Sisk-Gritz, a Marine Biology and Coastal Sciences major, are studying stress behaviors and how the environment and the seasons affect

the otters.

They know that Shelby likes to perform more than Han. Shelby flips and turns and plays to the crowd, whereas Han likes to get away and rest when too many people are around, they say.

Studying the otters’ behaviors has been fun but is also hard work.

“It really helps to get this experience – focusing step by step – and practicing applied science,” says Sisk-Gritz. “I feel more prepared for post-grad work or grad school.”

As Glaser puts it: “I’m learning how to be a scientist rather than just learning about science. That’s something we can all take along to all other disciplines.”

The Old Man of the Sea Lions

From a roof shed high above the sea lion exhibit, undergraduate students Camila Escobar, Evelyn Villada and Elisa Stone are observing J.R., Zeus and Porter’s swimming and interactions in the aquarium down below. Each student watches and logs the behavior of her assigned sea lion. The pod is all male because the zoo isn’t looking to breed them, animal keeper Angie Blanco explains later.

“They’re our babies,” says Stone, a Justice Studies major and Anthropology minor who is taking the course at a graduate level.

“The best part has been getting to know them,” says Escobar, who watches J.R., the “old man” of the pod. “When you make eye contact, it feels like they’re looking into your soul.”

Stone, who observes Zeus, agrees. “Definitely. You feel like you make a connection.”

At 32, J.R. is the oldest sea lion in captivity, according to the Species Survival Plan. Zeus is a “child” at 9, and 19-year-old Porter, who was introduced to the pod in December, is the rowdy “teen.” Zeus, the students agree, also is a bit of a bully.

Escobar says they’re on the lookout for and, of course, logging “any vocals, acts of aggression, different barks, activity on land, such as basking in the sun.”

She and Villada are both Biology majors and aspiring veterinarians.

“I’ve always been connected to animals,” says Villada, who works as a vet tech in Fort Lee.

Stone, who is graduate student Emily Rothamel’s research partner, will be interning at a law office this summer and is considering animal rights law. She took this class, she says, “because I will never have an opportunity like this again.”

Rothamel has been working at the sea lion exhibit since June 2021. Zoo officials knew that last fall they would be introducing the 800-pound Porter into the mix and her job was first to observe the behaviors of the other two sea lions before Porter’s arrival and then afterward, to note any changes in behavior.

“It’s great that I get to continue my research this summer and to be able to do it for so long. It’s invaluable as a grad student,” says Rothamel, whose graduate focus is marine biology, specifically sea lions and conservation.

The students’ data will provide animal keepers with a more accurate picture of the animals’ welfare, according to Blanco. “They provide a third eye and obtain constant research, which is only

going to better the well-being of our animals,” she says.

Blanco adds that the students’ research also will help other institutions. “It’s uncommon for a sea lion to live into its 30s, most only live into their teen years,” Blanco says. That’s why Rothamel and Stone are paying close attention to how J.R. behaves not only around Porter but in general.

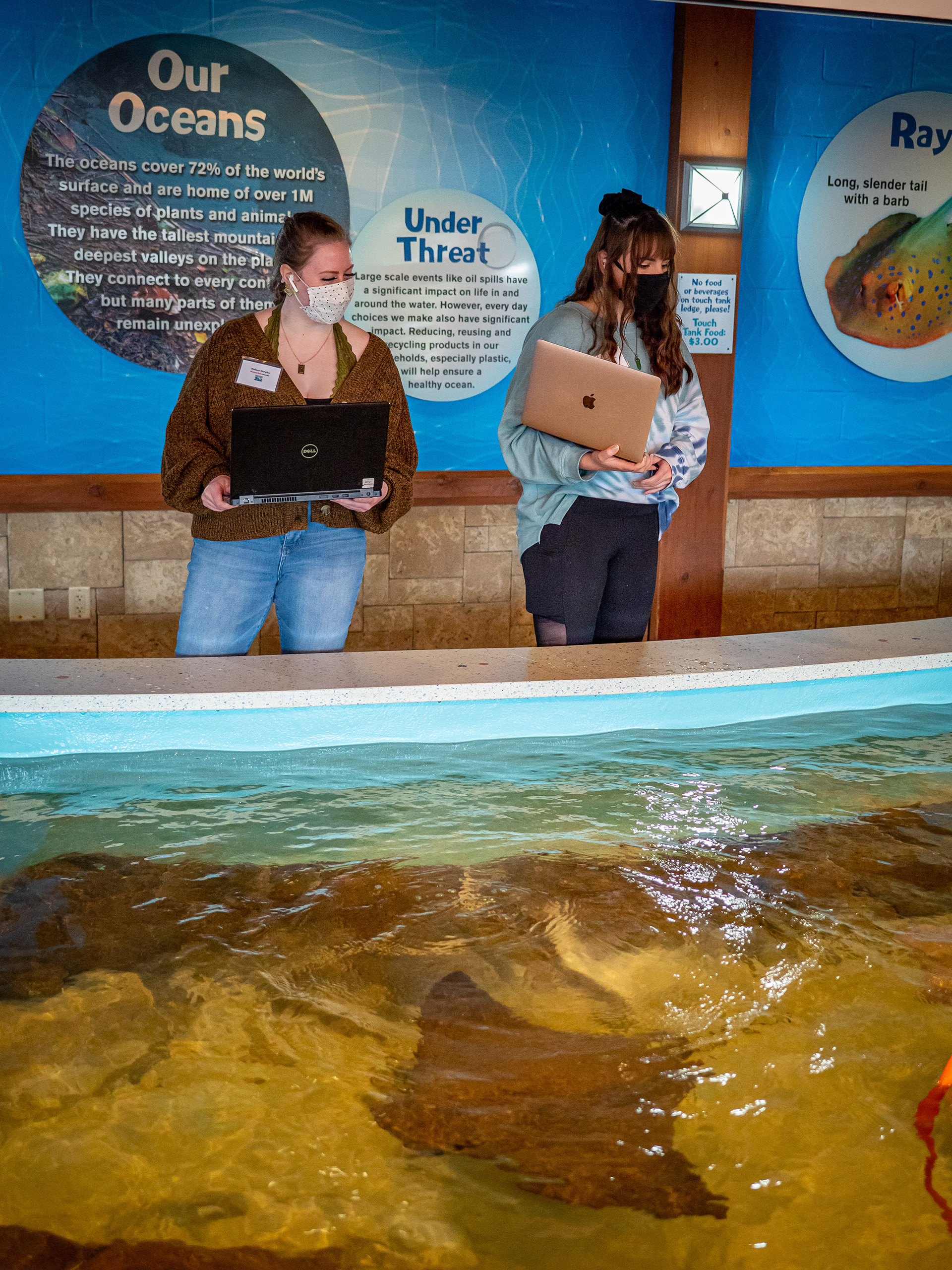

Enjoying Some Rays

At the cownose ray touch tank, senior Anthropology and Psychology major Melissa Matyiku and graduate Biology student Lauren Hope have gotten to know the behaviors and swim patterns of the rays quite well.

One ray in particular, a female named Sugar, swims around the edge in a repetitive pattern, letting visitors touch her back as she glides along.

“Sugar’s mom and her baby are both in this tank – so three generations,” says Matyiku. “It’s nice to have an off-campus experience, where we are connecting what we’re learning around the animals to what we’re learning about in the lectures.”

Hope’s focus is how human contact affects the reproductive behavior of the female rays, including how active they are in the tank when humans are around. Since her area of study is biology, ecology and evaluation of animal behavior, “this is a great class for that,” she says.

Director Fazio, who has enjoyed the collaboration, says if it were up to her, Turtle Back Zoo would partner with Montclair every semester.

“I would like to grow and expand this program,” she says. “This is a template for partnerships with other organizations and provides the next generation an opportunity to be involved in the conservation of some of the most precious species on our planet.”

Borgerson would love such an arrangement. “The students are going above and beyond every day to use their skills to change the world.”