Changing Lives

College students help prisoners work to obtain their high school diplomas, improve their futures

To get to the law library of the Northern State Prison in Newark, visitors must walk through a metal detector, a security check, a few sets of steel, double doors, and past prisoners exercising behind the razor wire fence surrounding the yard.

The sound of the heavy doors locking shut can be unnerving for first-time visitors, even college students trained to know what to expect. But the prisoners awaiting the students’ help in passing high school equivalency tests quickly put their new tutors at ease.

“The first time you hear it, it dawns on you that there’s no way out,” says Ebony Coleman, a junior economics major. “But the inmates are so kind and so eager to learn; they’re very respectful, and I have never felt scared or threatened in any way.”

Thirty-seven people from Montclair State have volunteered to tutor inmates at Northern State Prison as part of the Petey Greene program, a project that began at Princeton University in an effort to change lives and reduce recidivism. Statistics show that inmates with diplomas are more likely to get jobs when they get out and less likely to return.

Justice Studies Professor Jessica Henry first connected the University with the Petey Greene program in 2015, and says that while helping to change the trajectory of prisoners’ lives, students are also transformed in the process.

“Slowly but surely, they are changing lives in meaningful ways,” Henry says.

Having begun in 2008 with only a couple of New Jersey colleges, the Petey Greene program now operates in seven East Coast states and the District of Columbia and uses tutors from 28 universities, including several Ivy League schools. Students from Montclair State, Seton Hall and Rutgers tutor at Northern State Prison.

“I’ve been so impressed with the tutors from Montclair State,” says Samantha Thoma, the Petey Greene field director for New Jersey. “Especially considering so many of them have other responsibilities – jobs and school. I love how passionate they are about what we do. It’s a really good fit.”

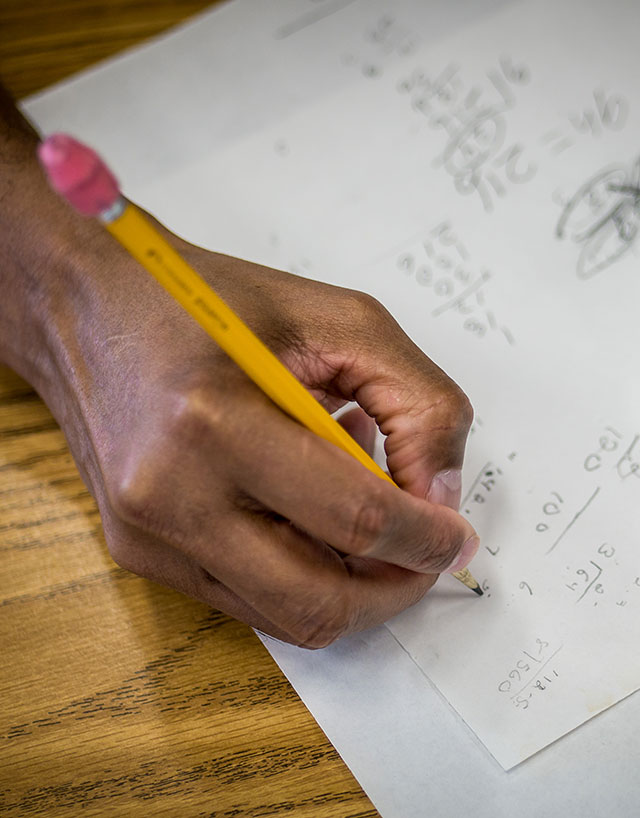

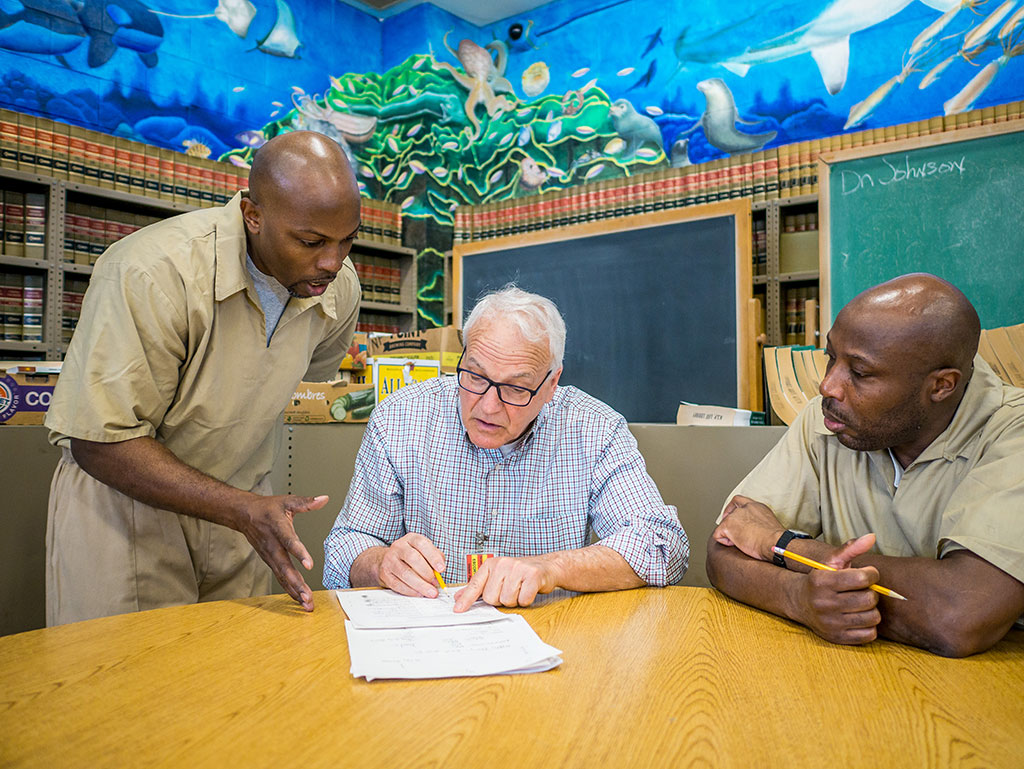

The law library at Northern State Prison is a large and sunny cinder block room with an ocean mural above shelves filled with law books. On any given weekday, several inmates and their tutors work on science, math, reading or writing. Each tutor spends about two hours a week at the prison.

“It helps their self-esteem to accomplish this,” says Janoa Watson, an athletic training major who started tutoring this spring as a freshman. “I enjoy pushing people to do their best, and I hope I can help them better themselves and improve their lives.”

Making the most of doing time

While their crimes are different, most of the inmates share similar educational backgrounds. None focused on school; many dropped out or were expelled. Most ended up in and out of detention, then jail and finally prison.

It took prison to change their mindset about education. Prison also gave them a place to learn without the distraction of the streets.

“Because of decisions I made, I’m forced to stay focused and handle business now. It’s [easier] to study now, because you want it,” says Edward Hawkins, 31, who is serving 18 years for aggravated manslaughter. “This program helps keep me on track.”

Prisoners are chosen based on good behavior and classroom effort. The one-on-one attention by tutors can mean the difference between passing and failing. It has also given inmates reason to think about the future.

David Valdez-Martinez, 54, grew up in Cuba and came to the United States at 17. He spent much of his adult life in and out of prison and is now serving an eight-year sentence for armed robbery. English is his second language, so he doesn’t always understand what is being taught in class. With Montclair State Justice Studies major Koedi Shakir’s help, he is now only seven points away from passing. Determined not to return to his previous life this time, he hopes to change things with a diploma.

“I’m planning to go to college when I get out,” says Valdez-Martinez. “I want to be an example for my kids, even though they’re grown. …I’m trying to be a better person.”

Shakir says she admires her “students” that want to change. “To me, they’re students not inmates,” she says. “They’re people, too, and they want to learn and do well.”

As a kid, Darrell Moody, now 43, was in special education classes, where he says he learned very little and was easily distracted. He skipped school to hang out in Newark with friends. He was constantly in and out of trouble – and jail. It wasn’t until prison, he says, that he was diagnosed with ADD and finally learned to read.

Now, with the help of a college student, he’s close to getting his GED. “I’ve been in every school program they’ve got,” says Moody, who is serving eight years on a manslaughter charge. “I had to get my mind together…I take all the programs I can take.”

Justice studies senior Lauren Vasquez once thought she would be a prosecutor, but after a year as a prison tutor, she decided to help inmates transition from incarceration to the community.

Vasquez has helped a few prisoners pass their tests. “The first one I tutored was very motivated,” she recalls. “He’d tell me about his goals and what he wanted to do when he gets out. When he passed his test, he was so grateful and thanked me for helping him. It was rewarding.”

Inmate Kevin McCray works as a teaching assistant. McCray, aka “V-1” for Victorious One, helps guide both inmates and students and the college volunteers when they have questions or need help with materials, etc.

“Slowly but surely, they are changing lives in meaningful ways.”

“It took prison to clear my mind and help me figure life out,” says McCray, 41, who was sentenced to 30 years for his role as an accomplice in a murder that occurred during a robbery. He decided the time would be best spent turning his life around. Eventually, he became a teaching assistant.

“Someone saw something in me that I didn’t see in myself,” says McCray, who hopes to one day work with troubled youth.

Educating, not judging

Tutors are trained in what to expect in a prison; how to interact with prisoners. They don’t ask about the inmates’ crimes or share their own personal information.

“Society portrays the incarcerated as less than human but the inmates I’ve tutored are not bad people. They’ve made some bad decisions and are paying the price,” says Coleman. “Who am I to judge you on something you did 25 years ago, before I was even born?”

Working with prisoners gave senior psychology major Gabriela Suriel a renewed appreciation of being free to make her own decisions. “It’s made me grateful to be able to step outside when I want to,” she says.

For most of the volunteers, tutoring is about giving someone a shot at a second chance. “[Tutoring] someone who wants to change their life for good is a humbling experience,” says Justice Studies senior Paramvir Singh.

Justice Studies senior Joe Wasowski says that, as a tutor, he enjoys pushing prisoners in the right direction. “It takes more than a handful of willpower for a middle-aged prisoner with a history of criminal behavior to decide that they care enough about their lives to educate and better themselves,” he says. “That’s…inspiring.”