Renaissance Man

English Professor

and literary scholar named a MacArthur “Genius” Fellow

Photo © John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, used with permission

Professor Jeffrey Alan Miller is excited about teaching even the most arcane texts in English literature. His interest, his passion is hard to contain. See it as he thoughtfully nods while speaking. See it as he paces the classroom in University Hall, punctuating the discussion as he exclaims his approbation to his students.

“Excellent!”...“Beautiful!”...“Exactly!”...“Nicole is on to something really important here.”

It’s not hard for Miller to be effusive in his praise. The two-dozen-plus students in his English Literature I: Beginning to 1660 class who are digging their way through Sir Gawain and the Green Knight are bright, attentive, prepared and engaged.

Although it is the first time this class has met since Miller was named a 2019 MacArthur Foundation Fellow – a “Genius Grant” awardee – on September 25, Miller downplays the honor. He briefly acknowledges the award – without even naming it – by apologizing for the MacArthur grant video in which scenes from the class are featured. He deflects the spotlight: “You’re famous now!” he tells the students. “The class looked great … although the video’s mortifying for me.”

A Brilliant Discovery

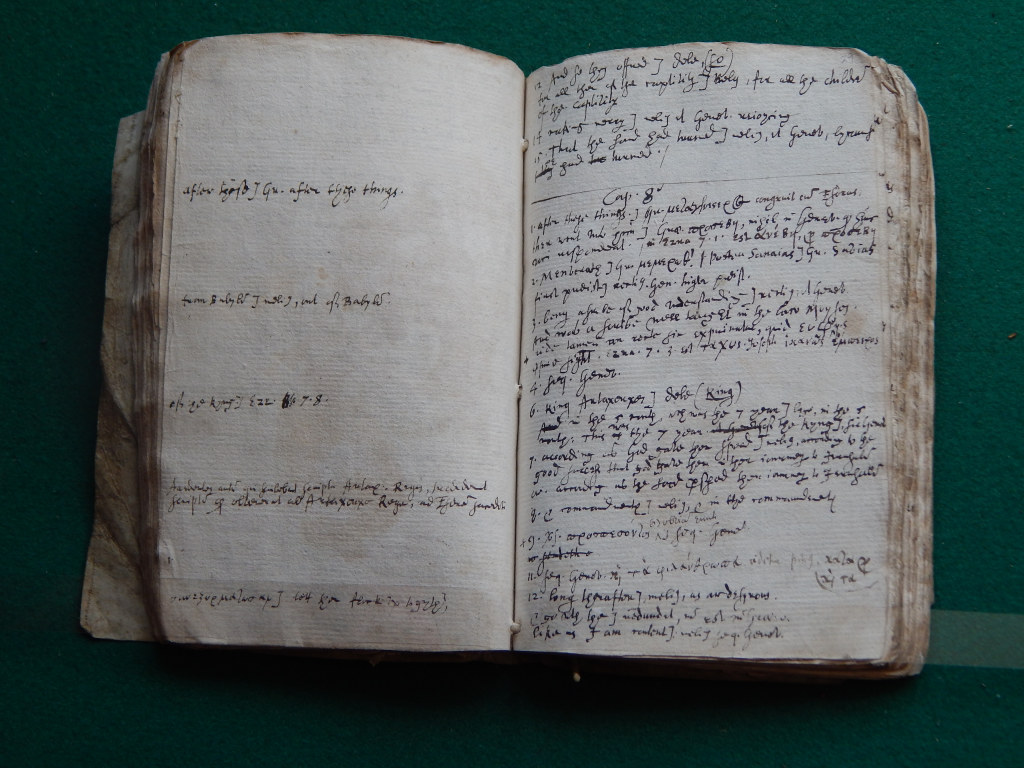

A Rhodes Scholar who attended Princeton University as an undergraduate and Oxford for his doctorate, Miller achieved international recognition in 2015 after discovering the earliest known draft of the King James Bible, which he identified while doing research in the archives of Cambridge University’s Sidney Sussex College. Published in 1611, the King James Bible is the most widely read work of English literature of all time and, it follows, one of the most influential. Experts characterized Miller’s discovery as being “perhaps the most significant archival find relating to the King James Bible in decades.”

The MacArthur grant ($625,000 distributed over five years) is the latest development in what has been an eventful year for Miller. Recently, he accepted one of two prestigious fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, both of which support a full year of dedicated work to complete a book-length critical edition and study on the discovered draft of the King James Bible.

“To be an English major takes a willingness to follow one's passions even in the face of such doubt that it is the best way to spend one's time and money.”

All these accolades could have gone to Miller’s head if it weren’t for the people who keep him grounded. Miller’s wife, Amy Bregar, is a gynecologic oncologist at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. Her job “throws into relief one’s own sense of self-importance,” says Miller. “She’s now an attending level physician. It’s a long road. Longer than my doctoral training by many years.” Miller and Bregar are parents to Abigail, age 1½. “She’s our pride and joy. Parenthood is truly the best thing.” Another girl is on the way.

A Place to Shine

Miller is also painfully aware of the difficulties facing academics, particularly specialists like himself, in finding situations that work for them professionally and personally – something he has time to contemplate on his weekly commute from Boston.

“I vividly remember the day I saw the job advertisement for Montclair State. There must have been this enormous smile on my face.” He credits now Deputy English Department Chair Naomi Liebler and Chair Jonathan Greenberg, among others, for championing the need for a Milton scholar. “Other universities have decided they can get by without someone who teaches Milton. You have to convince a dean, a provost, a president that they need someone who does Milton.”

In addition to his work on the King James Bible, Miller is also nearly finished with a book on John Milton, the 17th-century poet and author, most notably, of Paradise Lost. At Montclair State, Miller found a home where he could fly his Milton flag: “I could be myself. I didn’t have to pretend I was a different scholar.” It was Miller’s research on Milton that paved the way for his discovery of the King James Bible draft. While researching an essay in graduate school on Milton, Miller began exploring an archive of papers in Cambridge once belonging to Samuel Ward, one of the approximately 50 men appointed as a translator of the King James Bible. It was one of Ward’s surviving notebooks in the archive that Miller would later identify as containing a draft of part of the King James translation, which he discovered after returning to Cambridge to conduct additional research on Ward in 2014.

Students love Milton

Meanwhile, Miller’s work is hardly all dusty libraries and digital photographs of papers and manuscripts. Teaching is an equal calling to his research and writing, and the students feel it.

“From the moment he got here, people were signing up for Milton – which is unheard of,” says Liebler. “Within five minutes in his classroom, the students know they are in the presence of someone special.”

Students back that up. “He pushes us to analyze the text in ways we wouldn’t think. He made me a better reader,” says Zhane Daughtridge, a senior who first had Miller as a sophomore. She adds, “He never tells you you’re wrong, but tells you ways you could be right.”

Lauren Lamantia, a junior English major, wants to be a journalist: “He’s very involved in student conversation. He wants to hear our thoughts rather than his own.”

Christopher Condon, a senior English major, concurs: “There’s never a dull moment. He pulls in the students.”

The feeling is mutual. “The best part of being at Montclair State are the students by a mile,” says Miller. “They are so thoughtful, so passionate, so interested. They don’t take their education for granted. Many come from backgrounds where they cannot simply assume they will go to college. There is a palpable sense that the students are eager to learn, they want the education.

“Particularly the English majors have taken a risk – or so they are told by society – in being an English major. Study after study shows that’s not true. Still, to be an English major takes a willingness to follow one’s passions even in the face of such doubt that it is the best way to spend one’s time and money. As a teacher, it gives one a great sense of responsibility. The students expect to learn a lot. They deserve to learn a lot. I try to live up to my end of the bargain because they certainly live up to theirs.”

Age of Enlightenment

Born in Little Rock, Arkansas, and raised in Dallas, Texas, Miller, 35, was brought to the study of literature through a confluence of religion and intellectual curiosity. Growing up with an Irish Catholic mother and a Southern Baptist father meant religion was always a part of the discussion – but in an open-minded, inclusive manner.

“From the moment he got here, people were signing up for Milton. ... the students know they are in the presence of someone special.”

“I grew up in a house where religion and theology were taken very seriously,” he recalls. “It was regarded on an intellectual level, but also one did not have to think about it in a doctrinaire way.”

Miller notes that the Jesuits who taught at his high school were similarly open and interrogative and fostered his interest.

It was also in high school that he discovered what would become his calling – when he found his father’s copy of Milton’s Paradise Lost: “That was a transformative moment for me.”

Miller’s expansiveness is one reason the MacArthur Foundation selected him. “This year’s 26 extraordinary MacArthur Fellows demonstrate the power of individual creativity to reframe old problems, spur reflection, create new knowledge, and better the world for everyone,” MacArthur Foundation President John Palfrey said in a statement.

Some Notable Macarthur "Genius" Fellows

- Cormac McCarthy,writer, 1981

- Henry Louis Gates Jr.,literary critic, 1981

- John Sayles,filmmaker, 1983

- Marian Wright Edelman,children’s rights activist, 1985

- Harold Bloom,literary critic, 1985

- James Adolph Westfall,astronomer, inventor, 1991

- Twyla Tharp,choreographer, dancer, 1992

- Tim Berners-Lee,computer scientist, 1998

- Cecilia Munoz,Civil Rights policy analyst, 2000

- Colson Whitehead,writer, 2002

- David Simon,journalist, screenwriter, producer, The Wire, 2010

- Jad Abumrad,Radiolab host, producer, 2011

- Junot Diaz,novelist, 2012

- Ta-Nehisi Paul Coates,author, journalist, 2014

The foundation notes that Miller’s research focuses on “the emergence of key ideas about the role of faith in daily life and government among Reformation and Renaissance scholars.” In addition, “Miller’s expansive view of the writing process and of what constitutes a draft manuscript are changing our understanding of seminal works at the foundation of modern Christianity, philosophy, and literature.”

Defense of Freedom

Miller further explains why his approach to studying Milton is relevant now.

“Milton is one of the greatest authors who ever lived and wrote in any language. I personally think that Paradise Lost is the greatest work ever written. It never stops being relevant. Wrestling with reading, delighting in, thinking hard about, writing about, discussing one of the great achievements in human history justifies itself. It proves rewarding on its own terms. Beyond that, however, I do think that there is something really notable and pertinent to our present moment about Milton. Milton is explicitly invested in questions of freedom: social and individual freedom, freedom of thought, freedom of the press. He’s very much a free thinker about religion, government and society. He also asks, ‘Is personal freedom always a good unto itself? What does it mean to live in a society, country, nation? What rights should people have? Who should decide?’ These are questions that are very relevant today.”

Miller quotes Milton’s Areopagitica: “Where there is much desire to learn, there of necessity will be much arguing, much writing, many opinions; for opinion in good men” – by which, Miller believes, Milton meant all people, from the past to the present and into the future – “is but knowledge in the making.”