Eyes on the Prize

Former Red Hawk and police officer hopes to bridge the gap between law enforcement and urban communities

Shyquira Williams ’09

Shyquira Williams sat in her unmarked police car at an intersection in Camden, surveyed the desolate and depressing scene around her in one of the country’s most dangerous cities, and had an epiphany.

It was her second year as a detective in the city handling serious crimes such as sexual assaults and domestic violence in the special victims’ unit. Since it took her just eight months to receive that coveted promotion, she knew she was on the fast track to an even bigger role inside the police department.

But, that night in her sedan, something didn’t feel right.

“I remember that moment like it was yesterday,” recalls Williams, who graduated in 2009. “I looked around and saw the forest and not the trees. I said, ‘How? How do we have, in this urban community that is eight and a half square miles, such suffering? So much poverty? Such inadequate education and housing?’

“You have panhandlers begging for money, prostitutes trying to get their fix, people struggling with addictions. You have school kids stepping over needles, empty drug bags, kicking a beer can all the way to school. I just questioned how we have this in America. Why is this not on the top of the list for us to change? Why is this not a national problem that we’re trying to address?”

Williams continued her climb up the law enforcement ladder, moving to the Burlington County Prosecutor’s Office where she worked undercover on a team that handled narcotics- and gang-related crimes, but she couldn’t shake the feeling she had that night in Camden. Then, in 2017, she made a decision that changed her life.

She wanted to be a bigger part of the solution. So she left her job, entered the doctoral program at Stockton University and started her own foundation. She resolved to tackle one of the biggest problems in the country: finding a way to bridge the gap between urban communities and the police.

“I want to be a professor,” says Williams, who is pursuing her doctorate in organizational studies. “I want to create a program that combines criminal justice and African American studies. I want to be part of that change, and I think I can do that.”

No one who knew her during her days at Montclair State will doubt that statement. Williams, a Plainfield native, was an undersized guard on the women’s basketball team who went from academic probation as a freshman to the Dean’s List the next season. But the biggest lessons for “Shy,” as she is known, came off the court and outside the classroom.

It was at Montclair State where Williams found a passion for community service. It didn’t matter what it was – a team clinic with middle schoolers, a sorority event with sick kids – Williams loved making a difference in the University community. That passion made her one of her coach’s favorite players.

“One of the best things about Shy’s story is that she didn’t come in as a freshman with everything figured out or put together yet,” says that coach, Karin Harvey. “Like so many young women, she faced adversity and challenges. But she had great role models in her mother and grandmother, who were both strong women and empowered Shy to speak her mind and stand up for what she believed was right.”

Williams decided to honor one of those role models soon after graduating from Montclair State in 2009. She launched the Annie Lee Jones Foundation in Plainfield in her great-grandmother’s memory, an organization dedicated to making sure students have the tools they need to succeed academically and professionally.

That grassroots effort would have pleased Jones, who always had a plate of food ready for a hungry friend or stranger and whose favorite phrase was “pay it forward and it pays back.” Williams was touched that her grandmother, Tessie Jones, volunteered the most to pass out fliers advertising fundraisers such as walk-a-thons at local businesses.

But Williams didn’t stop there. She discovered, after taking a public speaking class her freshman year at Montclair State, that she had a knack for reaching young people. Williams now tries to speak to as many church and youth groups around the state as possible, spreading the word about empowerment.

“Look at reality TV today: You don’t get a lot of Michele Obamas out there,” Williams says. “I know when I go to these speaking engagements I get looked at up and down because they may not have seen a woman like me. All I want is to leave a lasting impression.”

That isn’t difficult, given her many hats. Beyond her past police work, Williams is also a lieutenant in the New Jersey National Guard and a published author whose children’s books, Proud Black Girl and Proud Black Boy, extol the same positive message she delivers in her speaking gigs.

The books. The foundation. The public speaking. It is hard to believe that Williams has the time to tackle a dissertation, but her academic work focuses on the impact she wants to make in urban communities.

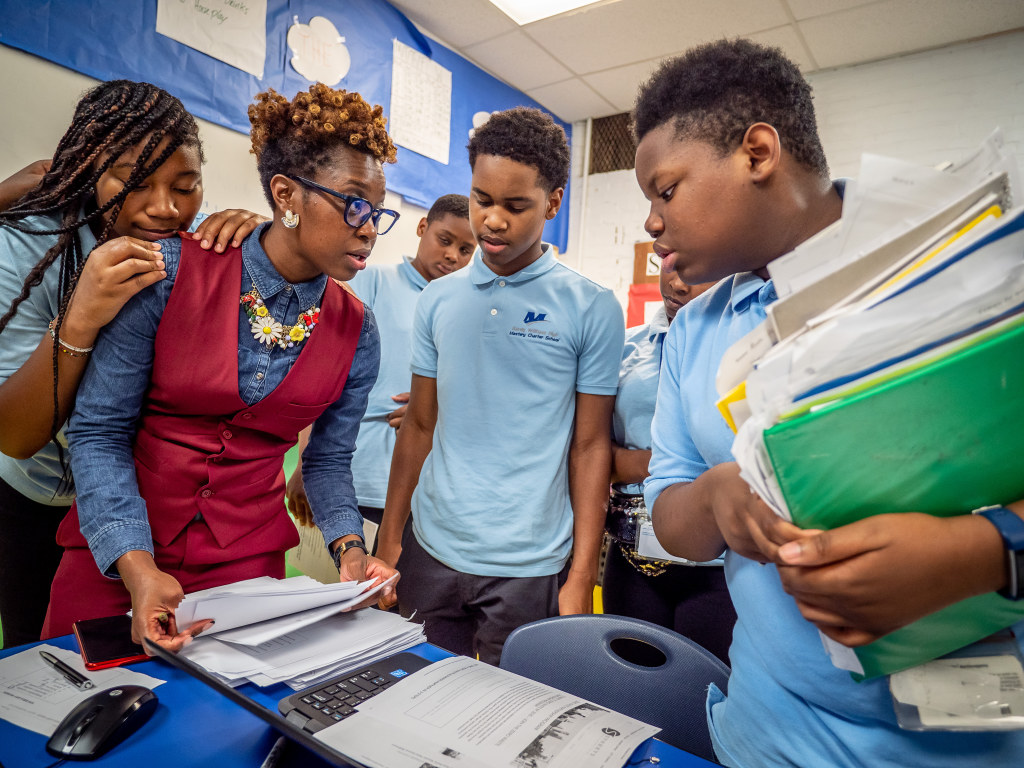

“I want to teach kids how to interact with the police,” she says. “I go to different urban communities, schools, and I teach them, ‘This is what you should do, and this is what you should not do.’ I want to help bridge that gap between the African American communities and law enforcement.

“We have to evolve with the times. We can’t sit here and rely heavily on what we’ve done in the past and think we’re going to change. That’s what my dissertation is now: how do we build awareness on both ends – not just the African American community, but how do we make changes on law enforcement as well? Because if one side changes and the other stays the same, that is not sustainable.”

That epiphany from her idling detective’s car all those years ago has led to a life’s mission – and it’s all part of a journey that started at Montclair State. If Shyquira Williams has it her way, she’ll be able to return to that Camden intersection someday and see meaningful change in one of the country’s toughest cities.