Solving Cosmic Mysteries

Faculty on LIGO team help with historic detection of neutron stars’ collision

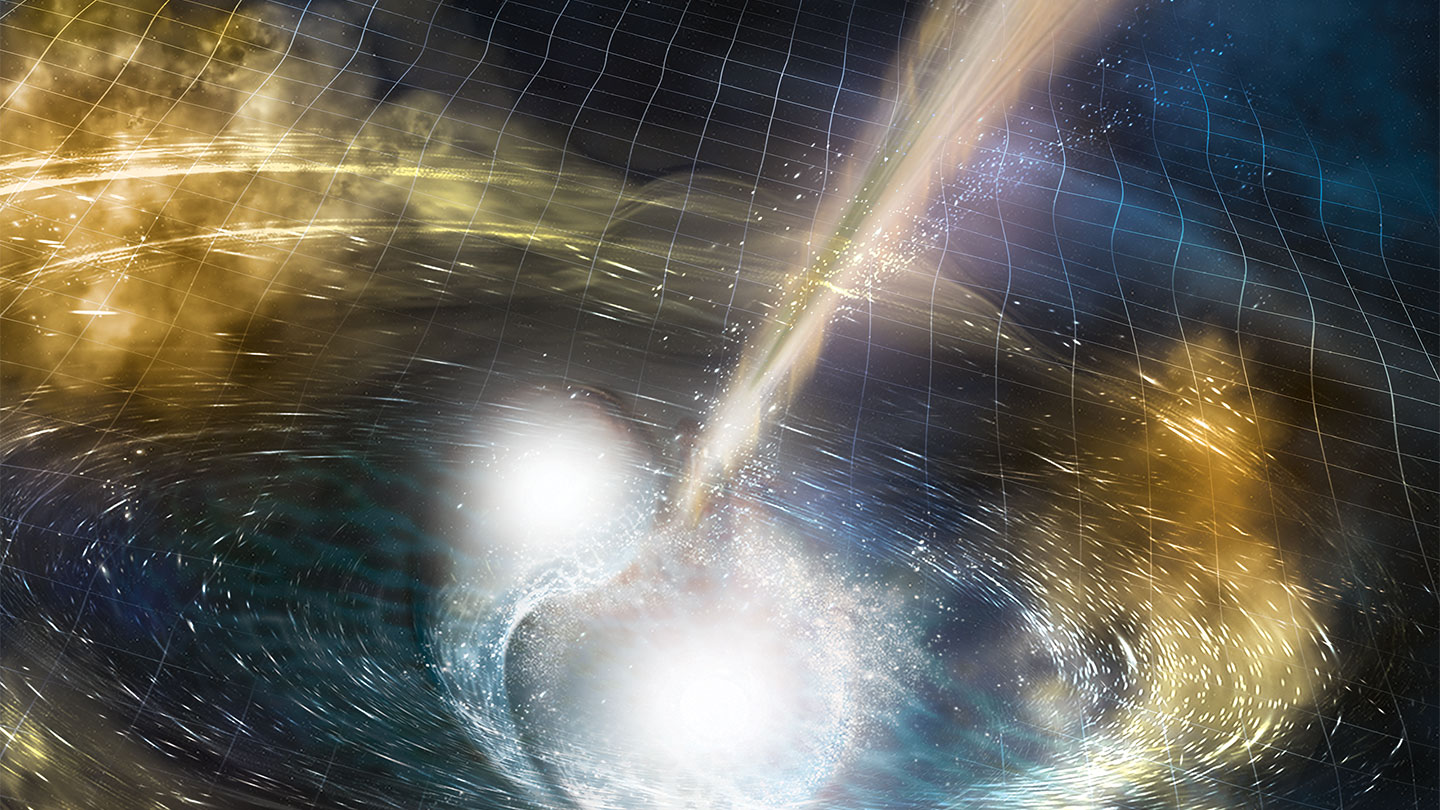

An illustration of neutron stars colliding, courtesy of LIGO

In a galaxy 130 million light years away and long ago, two neutron stars collided and collapsed into each other. But it wasn’t until August 17, 2017, that scientists were able to detect the ripples of the gravitational waves and light produced by that collision – a cosmic first. The historic discovery was made using the U.S.-based Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO); the Europe-based Virgo detector; and some 70 ground- and space-based observatories.

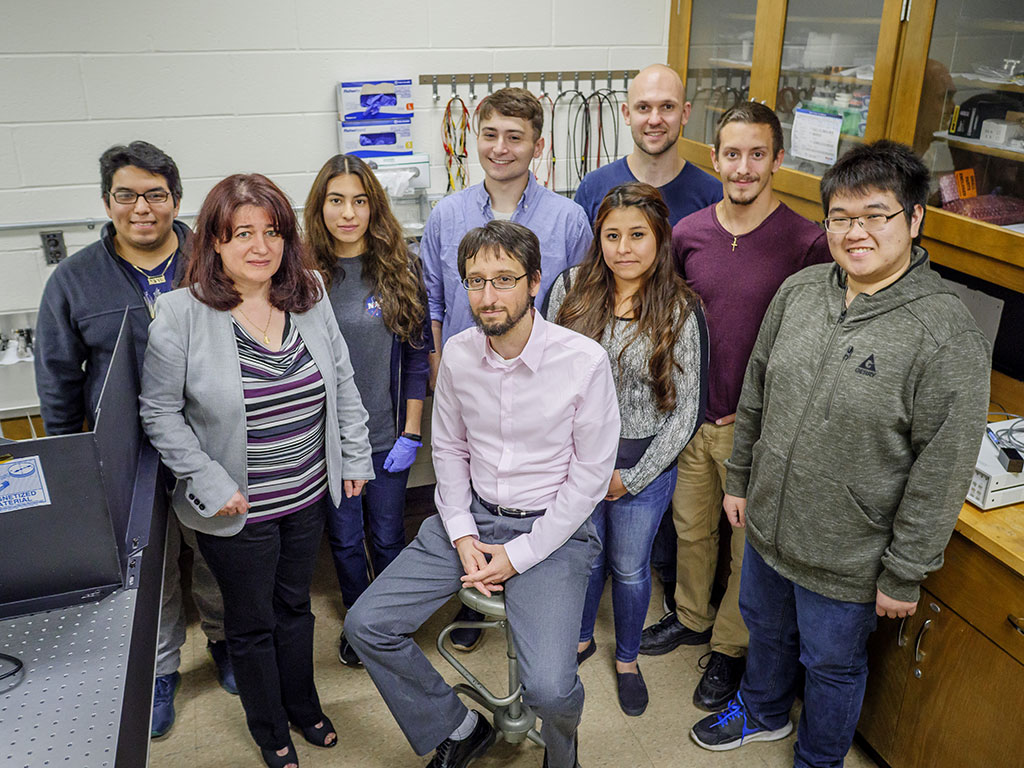

Montclair State physics faculty members Rodica Martin and Marc Favata are part of the international LIGO Scientific Collaboration team that made the discovery. A national- and state-designated doctoral research university, Montclair State has been a member of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration since 2013.

“We are proud to have two members of the LIGO team at Montclair State,” says College of Science and Mathematics Acting Dean Lora Billings. “Their contributions in unraveling the information provided by gravitational waves is a great example of the cutting-edge, collaborative research done in the College. The project also provides unique opportunities for our talented students. We hope that their amazing success continues.”

In addition to it being the first time the collision of two neutron stars – small, dense stars formed when huge stars explode in supernovas – has been detected using gravitational waves, it is also the first time a gravitational-wave signal has been accompanied by coincident detections with conventional telescopes.

“It is tremendously exciting to experience a rare event that transforms our understanding of the workings of the universe,” says France A. Córdova, director of the National Science Foundation, which funds LIGO.

While averaging just 12 miles in diameter, neutron stars are so dense that a teaspoon of neutron star material has a mass of roughly a billion tons. In a distant galaxy, two neutron stars spiraled toward each other, emitting powerful gravitational waves before they crashed into each other, causing a burst of gamma rays. Their collision produced a “chirp” recorded by the LIGO and Virgo detectors that lasted nearly 100 seconds. This happened 130 million lightyears away, in a galaxy 50 times farther than the Andromeda galaxy – the nearest major galaxy to the Milky Way.

A momentous breakthrough

“This is a really big deal,” says Favata. “Neutron star collisions are one of the key sources that LIGO was hoping to observe – and now we have. It’s also the loudest source that our network of detectors has found so far.”

According to Favata, the discovery has resolved a persistent mystery as to the origin of short-duration gamma ray bursts (GRBs). “It’s long been suspected that these GRBs are due to the collision of two neutron stars, but that hasn’t been confirmed until now.”

The new observations also resolve long-standing speculation as to how heavy elements, such as gold and lead, are produced. A byproduct of the collision of the two neutron stars, these elements are distributed throughout the universe.

Equally important, Martin says: “The discovery involved lots of electromagnetic astronomers, all working together with LIGO/Virgo. Making joint observations with these partners has been a key goal for LIGO.”

Confirming Einstein’s theory of relativity

On August 17, LIGO and Virgo detectors registered gravitational waves – or ripples in the geometry of space and time – at roughly the same time that NASA’s Fermi space telescope detected a burst of gamma rays. The discovery prompted follow-up observations by telescopes around the world.

Together, the gamma-ray measurements and gravitational-wave detections provide further confirmation of Einstein’s theory of relativity, which predicted that gravitational waves travel at the speed of light. In 2015, LIGO’s detection of gravitational-wave signals resulting from the merger of two black holes first validated Einstein’s theory and ushered in the new field of gravitational-wave astronomy. Earlier this month, LIGO founders Rainer Weiss and Kip Throne, as well as early LIGO Principal Investigator Barry Barish, received the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics.

Contributing to a groundbreaking discovery

As part of the approximately 1,200-member LIGO team, Favata and Martin helped contribute to its successes.

Martin helped to design and install various components of the upgrade to the detectors – called Advanced LIGO. “My role in the discovery was to help build the upgrade that enabled the recent discoveries,” she explains. “My current role is to develop and design optical components and instrumentation for future detectors. This will increase the sensitivity and allow us to observe even more distant events or sources that are currently too weak to detect.”

“Neutron star collisions are one of the key sources that LIGO was hoping to observe – and now we have. It’s also the loudest source that our network of detectors has found so far.”

Favata helped develop some of the gravitational-wave models used to analyze neutron star collisions. He and Martin are also actively involved in education and outreach efforts on behalf of LIGO. These include the soundsofspacetime.org website, which is being updated with sounds from the new detections, as well as informative exhibits of LIGO science. Both professors work closely with a team of eight students on experimental, theoretical and educational aspects of gravitational physics. The team is composed of undergraduates Valerie Avendano, Kevin Chen, Lita de la Cruz, Xavier Euceda, Nicholas Provost and Kevin Santiago, and graduate students Joseph DeGaetani and Matthew Karlson.

“This detection opens the window of a long-awaited ‘multi-messenger’ astronomy,” says Caltech’s David H. Reitze, executive director of the LIGO Laboratory. “It’s the first time that we’ve observed a cataclysmic astrophysical event in both gravitational waves and electromagnetic waves – our cosmic messengers. Gravitational-wave astronomy offers new opportunities to understand the properties of neutron stars in ways that just can’t be achieved with electromagnetic astronomy alone.”

More details are available at ligo.org