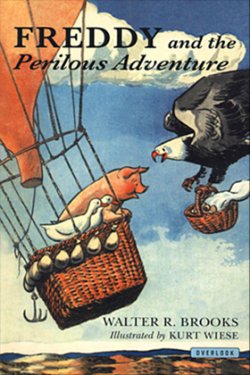

Artwork by Shawn Harris from The Eyes and the Impossible

© 2023 by McSweeney’s

Reviewed By Peter Shea

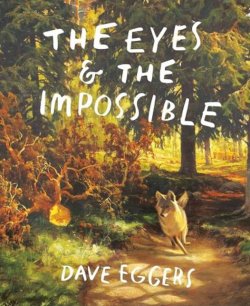

Johannes, the dog narrating The Eyes and the Impossible, lives on the animal side of a nature park – its own society, the local establishment, like the permanent residents in a resort community. His world owes something to all the great talking animal books. For me, reading the story brings back memories of The Wind in the Willows, Charlotte’s Web, Beautiful Joe, and the adventures of Freddy the Pig. My critical faculties are aroused: did Eggers make the squirrel squirrelly enough? Is the animal world too human? Not human enough? Is the plot in some way believable – aside from the talking animals? I don’t usually regard talking animal books as provocations for thinking, though I am very glad they exist for the kind of thing they are – visits to other worlds, just a little skew from human space.

This book is more than it seems. Nicola Davies, reviewing for The New York Times, captured the way this story works: “We need brave, big stories like these, stories that help children (and adults) find their place in a sometimes frightening world” (April 21, 2023).

Johannes, the dog-narrator, has found his place: he runs, and sees. The first line of the story: “I have seen all of you here.” That line distinguishes The Eyes and the Impossible from every other talking animal book I know. These all focus inward, on a confined, simple, orderly life, to be maintained against disturbances and re-established after disruptions. An enduring group of family and friends keeps the main character safe. When Charlotte the spider dies, in Charlotte’s Web, she leaves her daughters to keep Wilbur company. The weasels are forced out of Toad Hall, in The Wind in the Willows, and life can go back to normal. The Piper at the Gates of Dawn points beyond the simple life of Rat and Mole, and, for that reason, makes them forget meeting him, so that their lives won’t be disturbed.

These animals, by contrast, seek out novelty. Johannes is the scout for the guardian bison, charged with finding out what’s new, so that adjustments can be made: the raccoons can be counseled to move out of the way of the new road. But that’s just the beginning of his adventures. Johannes is fascinated by paintings, though he doesn’t know why. He questions the tradition of noble suicide among his seabird friends, when long flights are no longer possible: is it really so terrible – to walk? The arc of the book challenges the limit on the lives of the bison, who just receive reports, but never go on adventures – a limit that looks absolute, at the start of the story. It also challenges the conception the animals have of their world as the whole world; they come to realize that they live on an island, and they begin to wonder what the mainland might look like.

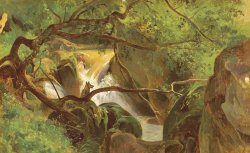

Artwork by Shawn Harris from The Eyes and the Impossible

© 2023 by McSweeney’s

Plato is famous for the myth of the cave, a story of regions of darkness and of the adventure of enlightenment, ending with a final vision of light itself. Plato is less famous for the myth of the hollows, in Phaedo: a story of imperfect perception giving way to better vision, giving way to yet better vision, with no end in sight. That’s the feeling I get from this book: the animals have not just discovered the limits of their ‘personal’ worlds; they have discovered transcendence, the possibility of always pushing the limits of any world they find themselves in, and of seeing themselves as “seeing everything” in an expanding universe – everything gets wider and wider, and doesn’t seem to ever reach a limit – and that prospect is presented as exciting, powerful, energizing.

I am inclined say to that The Eyes and the Impossible is not a book within philosophy. It is somehow the essence of philosophy – and science – and art – the human adventure, summarized. (Camus, with pictures.) I am so curious how children will take this, especially if they already know Charlotte’s Web and The Wind in the Willows and Freddy the Pig. It might be fun, with the right group, to ask what’s different about the animals in this book.

I have to say something about the pictures: the great masterpieces of art, to which Johannes the dog is deftly introduced. It makes the point: this animal is on the same great adventure that all these humans undertook, in all these different centuries, a journey to, and beyond, the limits of the possible.

We are in a favored position now, to think about animals: we know so much about their experimentation and thinking, their social innovations, their ingenuity, and all that testimony allows us to ask questions that would have been impossible for E.B. White and Kenneth Grahame: are there animal analogues to all the great human quests, to all the ways that some of us travel beyond our comfort zones, beyond our ‘normal,’ our ‘possible’? So, in that spirit, one might follow a reading of this story with a look at “My Octopus Teacher,” or some other careful treatment of animal thinking.

We are also, unfortunately, in a position now to know more than we want to about the consequences of non-transcendent thinking, the way that just taking account of one’s own safe little world makes one miss things. It is the genius of this book to question the longing for a safe, bordered, orderly world, to show what that ideal ignores. In that connection, one might move on from this story, with the right group, to watch The Zone of Interest, a dramatization of idyllic family life, right next to Auschwitz, in the family of the commandant.

It is difficult to imagine a more important contribution to literature for thinking children than The Eyes and the Impossible.