From An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children

© 2024 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Reviewed By Maughn Rollins Gregory

The common sunflower is the national flower of Ukraine and today is used around the world to symbolize Ukrainian national pride and resistance against Russia – the two countries that supply around 75% of the world’s sunflower oil. A Google search on the sunflower’s history in Ukraine turns up phrases like “The Spanish brought …” and “Spanish explorers introduced …..” But as the novelist and gardening writer Jamaica Kincaid and artist Kara Walker explain in their lush, insurgent new alphabetary (under the entry for Helianthus annuus),

This flower, so common to us now, is endemic (native) to the dry parts of the places we call Mexico, New Mexico, Arizona, and Texas. It was worshiped by the Aztecs; the Hopi extracted dyes from its seeds and also ground the seeds into a flour. The sunflower was introduced to Europe by rapacious Spaniards and to Russia by Peter the Great.

The natural history of plants is quite as philosophical as it is scientific—run through with ethical, aesthetic, political, and even metaphysical meaning.

Kincaid’s and Walker’s intention for their Encyclopedia is revealed in its subtitle, calligraphed along the bottom of the title page: “An Alphabetary of the Colonized World.” That also explains their selection of familiar and unfamiliar plants here, for in relating the origins, biological features, and uses of these particular plants, they simultaneously offer a primer on colonialism, slavery, and genocide. I can hardly think of a better way to introduce young children to this history and these ideas. And while the phrase “colored children” will strike some as regressive, Kincaid has explained that she prefers it to the phrase “children of color,” which seems to exclude White children, “because white is a color too.”

From An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children

© 2024 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Philosophizing about social justice involves what the Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire called learning how to ‘read the world’ – including our political, cultural, and personal histories – in terms of how power operates in it. An important part of this is acquiring what the American philosopher Leonard Harris (who created a philosophy for children program in Washington, D.C. in the 1980s) calls ‘the vocabulary of oppression’. Among the terms Kincaid and Walker introduce in their Encyclopedia are variations on:

Colonize • Conquer • Displace • Dispossess • Empire • Exploit • Genocide • Hanging • Injustice • Murder • Rapacious • Ravage • Slavery • Subjugate • Tyrannize • Violence • War

Importantly, none of these terms is defined here; they are embedded in Kincaid’s botanical histories and reflected in Walker’s artwork. For instance, the entry “B is for Breadfruit (Artocarpus altilis)” explains that this was one of many plants redistributed by British colonizers “to various parts of the Earth that shared a similar climate,” and notes that “This was all to the benefit of that bastion of evil known as the British Empire. The breadfruit was sent to the West Indies [where] it was regarded as a cheap source of food for the enslaved people on the Islands [who] apparently were taking time from their labors to grow food to feed their hungry selves.”

From An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children

© 2024 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

A few other Examples: France made so much money from indigo farms in colonized Haiti that after the revolution that freed enslaved Africans there, Napoleon Bonaparte was forced to sell the Louisiana Territory to Thomas Jefferson. When opium was banned by the Chinese in response to widespread addiction, Britain waged a war to force the Chinese to allow the importation of British opium in exchange for access to China’s silk, porcelain, and tea. “It would be as if Columbia and Mexico invaded the United States for the purpose of forcing Americans to buy cocaine and other addictive plants so they could have access to whatever it was the Americas had and they wanted.”

Sometimes the plants described are only symbolically related to oppression. The North American elm tree appears in Benjamin West’s painting Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, which helped to create the myth that William Penn negotiated and traded gifts for land belonging to the Lenni Lenape, who eventually “were dispossessed of their ancestral lands and made to seem strangers and wanderers in a world that wished and worked toward their complete disappearance.” Yucca brevifolia, commonly known as the Joshua tree, acquired that name,

from Europeans who were settling in that part of the United States, violently displacing the Indigenous population they met there. These settlers believed that this tree, with its unfamiliar form and arrangement of leaves and flowers, so abundant in the vast desert landscape, was a sign from God, giving them permission to continue their crime and claim the land that had previously belonged to the Indigenous people. It was not the first or the last time that a people called on the divine to justify an injustice.

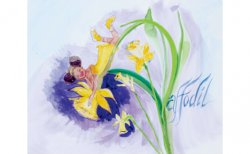

And William Wordsworth’s poem “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” was taught in schools across the British colonial empire to children who would never see a daffodil.

From An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children

© 2024 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

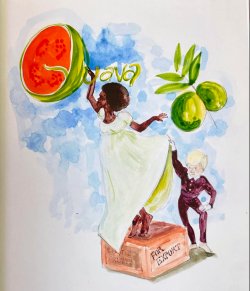

Sometimes historical oppression is depicted in the Encyclopedia’s art rather than its text. The entry for Hibiscus (Hibiscus rosa-sinensis) explains that “this shrub, native to the tropical area of China, is the national flower of […] many colonized countries,” and the illustration depicts a White woman lying naked on a bed, wearing Hibiscus flowers in her hair, attended by a Black servant. The entry for guava (Psidium guajava) explains that it originated in the Caribbean and Venezuela and that its sweet fruit is eaten raw and made into beverages, jams, and a sweet paste enjoyed by children. But the artwork depicts a Black girl in a long white dress standing on a box labeled “Exotic Fruits for Export” to reach for a guava fruit, not noticing a White boy behind her lifting her dress and looking up inside it—an oblique reference to the sexual violence involved in colonialism.

From An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children

© 2024 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

How we talk with our children and students about these histories will depend in large part on their age and experience. Kincaid and Walker have constructed their Encyclopedia in layers that invite careful excavation. On the surface are verbal and visual clues intended to prompt children’s questions that will open conversations leading to deeper levels of meaning in the book. It is well for adults sharing this book with children to be led by children’s curiosity, but it is just as well that we bring our own intentions to help them cultivate a vocabulary and historical understanding of oppression. For this purpose, the Encyclopedia usefully functions as a primer, provoking further investigations. For instance, in the entry for the flowering tree Franklinia alatamaha, the eighteenth-century Swedish physician, botanist, and zoologist who invented binomial nomenclature (genus and species) is referred to as “the notorious Carolus Linnaeus,” with no explanation. A cursory internet search reveals that Linnaeus was an early proponent of scientific racism, theorizing that Whites are, by nature, morally and physically superior to Blacks. Many entries in the Encyclopedia can also be compared to accounts of the same historical events in school texts and online resources, which will inevitably open questions about how history is written.

Inevitably, these conversations will produce feelings of horror, anger, shame, defensiveness, compassion, gratitude, and pride—about one’s national history, one’s ancestors, and one’s own socioeconomic situations and ways of life. Confronting these feelings is part of the continued legacy of these histories, and working out their meaning is the job of philosophy. It is important for adults to model for children that because these feelings are ethically and politically meaningful, we should not turn away from them, but carefully considered their appropriateness as responses to what we are learning, and consider, then, right ways of further responding, with meta-feelings and with actions.

One reason An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children works so well as a primer on human oppression is that it provides plenty of botanical natural history to support inquiry into natural philosophy. Common plant names are given with their Latin nomenclatures, enabling Kincaid and Walker to illustrate how many species are related to one another and how plants in one part of the earth are related to plants in other parts. The Rosaceae family, for instance, includes apples, strawberries, loquats, raspberries, and all other thorny-stemmed fruit-bearing plants. The mallow family, Malvaceae, includes cotton, hollyhock, hibiscus, okra, and cocoa. The use of Latin is explained in the entry “L is for Linnaeus. Carolus Linnaeus (or Carl von Linné, as he came to be known),” who saw the scientific need to standardize plant names around the world and used Latin because it was “the common language used by educated people of many different countries.” (Kincaid adds the perplexing idea that “the people for whom Latin was their native language had disappeared in the natural evolution of human beings meeting and destroying each other”). In addition to naming eight botanical families, Kincaid and Walker introduce variations on botanical terms including:

Annuals • Atmosphere • Bulb • Deciduous • Dicot • Germinate • Habitat • Herbaceous • Monocot • Perennial • Species • Temperate climates • Tuberous

The first entry in the Encyclopedia, “A is for Apple (Malus domestica),” suggests that when Adam and Eve ate the forbidden fruit, “they fell in love with the world around them, and understandably so, for they were in a garden.” Gardening is further encouraged in the entry on utensils, which defines them as “anything a gardener finds necessary for making the ground they are bent over yield to their desire.” And the entry “K is for Kitchen Garden” explains that “when we say we have a kitchen garden (or a vegetable garden), it is our way of reminding ourselves that we have – and can have – another garden, one that is full of trees and flowers ….” Significantly, Kincaid describes the gardener’s work in that garden as philosophical and spiritual, as well as manual: “That garden feeds and nourishes our souls and inspires us to think about ‘things’: the little doubts we harbor deep inside ourselves, our hatreds of others, our love of others, the many ways in which we can destroy and create the world and live with the consequences.”

From An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children

© 2024 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

References

Jamaica Kincaid, Jamaica, Kara Walker, and Hilton Als (2024) Live from the New York Public

Library: An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children. 7 May 2024. Broadcast on YouTube at

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZRc5oFHnBwQ&list=PLL6gs3aZKBap8fArHk2EdhwoEPZoWKPAt&index=7.

Smarthistory (2020) Teaching Guide: Benjamin West, Penn’s Treaty with the Indians. URL =

https://smarthistory.org/seeing-america-2/migration-and-settlement/teaching-guide-benjamin-west-penns-treaty-with-the-indians/.