An Audit of Food Security, Perceptions, and Experiences of Students at Montclair State University between 2022 and 2024, organized by Dr. Lauren Dinour, DrPH, RD, CLC and Andrea Uguna, MS.

Introduction

The Hunger Free Task Force

In 2016, a preliminary student-led survey identified a notable student need for food and other household necessities. As a result, in 2016, Montclair State University became the first four-year university in New Jersey to open an on-campus food pantry: the Red Hawk Pantry. In 2019, University researchers Chris Snyder and Dr. Lauren Dinour initiated the first administration of a standardized food security survey to the University’s student population. This survey was intended to inform program developments to projects overseen by Snyder and Dinour. Information from this survey highlighted areas of student need, and contributed to the formation of the Montclair State University Campus Hunger Free Task Force. The Hunger-Free Task Force is composed of University organizations and staff dedicated to addressing the issues adult students face while pursuing higher education at Montclair State University.

This report was authored for the Montclair State University Campus Hunger-Free Task Force, and its constituents:

- Auxiliary Services

- Food Recovery Network

- Gourmet Dining

- Hunger Free Campus Taskforce

- Office of the Dean of Students

- PSEG Institute for Sustainability Studies

- Red Hawk Pantry

- Residence Life

- Student Development and Campus Life

- University Facilities

It is intended to provide guidance to these University organizations in identifying and addressing student food needs, including, but not limited to: food insecurity; lack of access to culturally, religiously, allergically, or nutritionally appropriate food; and emergency food needs. This report provides necessary updates to the University statistics on student food security, including the prevalence of student food insecurity and student perceptions of the campus food environment. This report also sets, and contributes to, a baseline measurement which has been standardized to allow for comparison between this and other populations (i.e., by utilizing a modified version of the standardized USDA Household Food Security Survey Tool), and allows for follow-up surveys to be performed in order to measure progress made towards addressing student food security by the above mentioned campus entities and others, as identified.

Timeline

Below is a timeline of events related to the Montclair State University Campus Hunger Free Task Force and its component organizations.

- 2016

- Student-led research, as part of a capstone project, investigated student difficulty in purchasing household necessities, toiletries, and food.

- Montclair State University opens the Red Hawk Pantry, an on-campus food pantry for student use.

- 2017

- The Montclair State University chapter of the Food Recovery Network is established, with Dr. Lauren Dinour as Faculty Advisor.

- 2018

- The Montclair State University Campus Community Garden was established, led by Chris Snyder as garden coordinator.

- 2019

- Chris Snyder and Dr. Lauren Dinour administered the USDA household food security survey. All enrolled students were invited to participate, and results indicated that 44% of respondents were experiencing food insecurity during the Spring 2019 semester.

- Later that year, the campus established the Hunger-Free Task Force, composed of representatives from Dining Services, Student Development & Campus Life, Dean of Students Office, faculty, and students.

- 2020

- Beginning of the COVID-19 Pandemic.

- Students leave campus for remote learning.

- 2021

- Montclair State University designated by the State of New Jersey as a Hunger-Free Campus, in acknowledgement of University’s dedication and progress towards addressing student food needs.

- Montclair State University received its first grant from OSHE to expand hunger-fighting efforts.

- As part of the grant, Swipe Out Hunger was introduced on campus, allowing students enrolled in a dining block meal plan to donate up to two block swipes per semester to support other students struggling with food insecurity.

- 2022

- Students return to campus for in-person instruction.

- Further efforts rolled out, such as the establishment of a Hunger-Free Campus website, hiring of a case manager to assist students in applying for NJ SNAP, and provision of weekly shuttles to and from local supermarkets.

- 2023

- Second OSHE grant received.

- Record demand at Red Hawk Pantry.

- 2024

- Third OSHE grant received.

- Food Recovery Network provides meals for Red Hawk Pantry.

Interpreting the Audit

Several terms with specific programmatic definitions are used within this report, and are defined below. Please refer to the appropriate definition for each of the referenced data sources.

According to the United States Census Bureau, a household includes all the people who occupy a housing unit (such as a house or apartment) as their usual place of residence. A household includes all of the related family members and all of the unrelated people, if any, such as lodgers, foster children, wards, or employees who share the housing unit. A single person living alone in a housing unit, or a group of unrelated people sharing a housing unit such as partners or roommates, is also counted as a household.

For the purposes of allocating nutritional support services, the United States Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service defines a household as all the people who live together, and who purchase and prepare meals together. Households will include some members (such as spouses and most children under age 22) even if they purchase and prepare meals separately. If a person is 60 years of age or older and unable to purchase and prepare meals separately because of a permanent disability, the person and the person’s spouse may be a separate household if the others they live with do not have very much income.

The United States Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service categorizes household food security status into four ranges, defined below:

High Food Security — Households had no problems, or anxiety about, consistently accessing adequate food.

Marginal Food Security — Households had problems at times, or anxiety about, accessing adequate food, but the quality, variety, and quantity of their food intake were not substantially reduced.

Low Food Security — Households reduced the quality, variety, and desirability of their diets, but the quantity of food intake and normal eating patterns were not substantially disrupted.

Very Low Food Security — At times during the year, eating patterns of one or more household members were disrupted and food intake reduced because the household lacked money and other resources for food.

An individual that identifies experiencing high food security or marginal food security is considered to experience food security, or be food secure; an individual that identifies experiencing low food security or very low food insecurity is considered to experience food insecurity, or be food insecure.

Montclair State University Student Food Security to Date

Audit Methodology

To assess food security, we utilized an anonymous, online, cross-sectional survey conducted via Qualtrics. Surveying started 30 days after the semester began and continued until the last day of classes. All enrolled students were invited to participate though participation rates varied by semester, with 12.1% of enrolled students responding to the survey in Fall 2022, 10.1% in Spring 2023, and 5.9% in Spring 2024. The survey included demographic questions and the United States Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) 18-item household food security measure. Descriptive statistics and logistic regressions were used to determine the prevalence and predictors of food insecurity each semester.

Demographics

Survey participants largely consisted of students aged 18-23 years, with a majority identifying as female and White or Latino/a/x. About half of participants were employed, many working 20+ hours per week. Just under half of participants were first generation college students, and about two-thirds had been in school for more than a year. Most students reported that their grade point average (GPA) was at least 3.0 on a 4.0 scale. Additionally, one of every four to five participants indicated that they did not have enough time to eat before class.

Student Food Security Status To Date

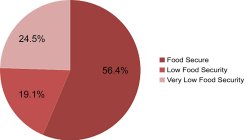

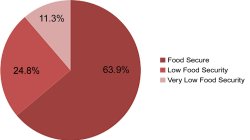

Across the three semesters (Fall 2022, Spring 2023, and Spring 2024), food insecurity affected nearly half of students surveyed. Food insecurity includes both low food security and very low food security, the latter of which is the most severe. At Montclair, very low food security was consistently reported by over a quarter of participants. These levels greatly exceed national averages (in 2023, 13.5% of U.S. households were food insecure).

High-Risk Groups

Students at the highest risk of food insecurity consistently identify as:

- Genderqueer

- Black or African American

- First-generation college student

- Report not having enough time to eat before class

Additionally, students living at home with a parent or guardian were at lower risk of food insecurity across all three semesters.

Food Insecurity Solutions at Montclair

Montclair State University has implemented several initiatives to combat food insecurity, including:

- Hunger-Free Campus Task Force: A collaborative campus effort to address student food insecurity

- Red Hawk Pantry: Supplies food and personal care items to students, faculty, and staff in need

- Food Champion Program: Alerts participants of surplus food from catered meetings and events

- Food Recovery Network: Recovers excess food from campus dining and provides to the Pantry

- Swipe Out Hunger: Allows students to donate two meal swipes to peers facing food insecurity

- Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP): On-campus assistance with SNAP enrollment

- Supermarket Shuttle: Free transportation from campus to local supermarkets that accept SNAP

Recommendations for Additional Efforts

Food insecurity remains a pervasive issue at Montclair State University, affecting a substantial portion of the student body. High rates of food insecurity, especially very low food security, highlight the need for continued and enhanced efforts. The association between student food insecurity and various demographic and socioeconomic factors suggests that interventions must be targeted and multifaceted.

- Increase Awareness: Utilize multiple communication channels, including social media, university platforms, and information sessions to raise awareness about available food security resources.

- Targeted Support: Develop programs specifically designed for high-risk groups, such as genderqueer students, Black or African American students, and first-generation college students.

- Expand Food Access: Implement mobile pantries and satellite locations across campus to increase food assistance accessibility.

- Financial Literacy and Meal Planning: Offer workshops to help students manage their resources effectively and make health and informed food choices.

- Cultural Sensitivity: Collaborate with local community organizations to provide culturally-appropriate food options for international and minority students.

Next Steps

The ongoing prevalence of food insecurity at Montclair State University calls for a sustained and integrated approach, ensuring all students have access to the resources necessary for a healthy and successful academic career. Food insecurity trends will continue to be monitored through regular surveys, with consideration of expanding data collection efforts to include more qualitative insights into students’ experiences. Collaboration with other institutions to adopt innovative food security initiatives could also enhance the effectiveness of current programs. Additionally, Montclair should explore further funding opportunities and partnerships to support new and ongoing food security efforts.

By implementing recommendations detailed in this report and learning from other campuses, Montclair can make significant strides in reducing food insecurity and improving the well-being of its students.