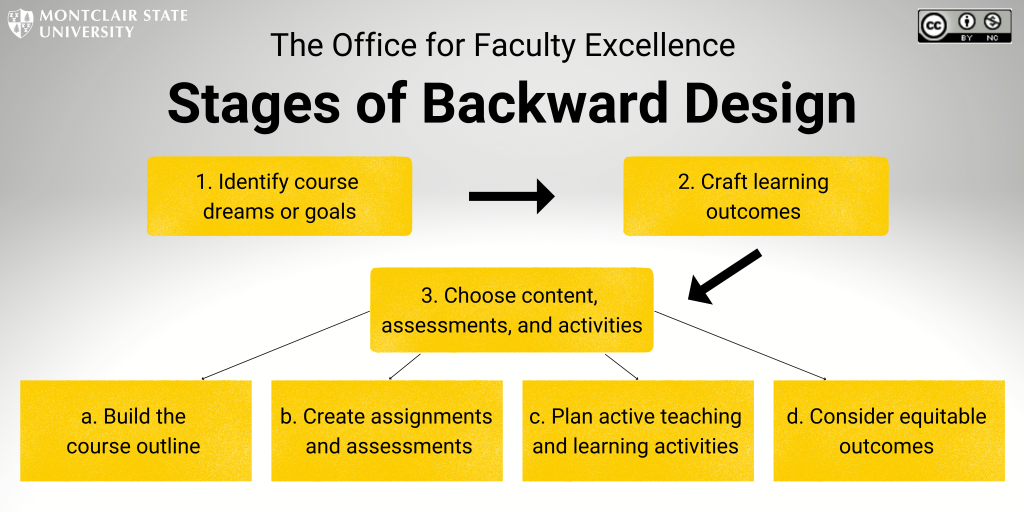

Using backward design ensures the essentials of a strong course: student learning outcomes, a course outline, assignments, assessments, and learning activities.

Backward Design

Good courses are often designed from the end: by imagining what students should have learned before choosing the materials and activities that will help students achieve those learning goals. In this backward design model, as McTighe & Wiggins describe in their work Understanding by Design, instructors define their learning goals and outcomes first, and then build out the course content, assignments, assessments, and learning activities.

As you begin to build your course, use these steps to define clear, measurable learning outcomes, and then structure and populate your course with appropriate activities, assignments, assessments, and content.

- What big, essential, intellectually challenging questions will your course help students answer and retain?

- What abilities or knowledge will this course help students develop or acquire?

- What will students be able to do, know, think, or appreciate by the time they finish your course?

How will this course develop and support students’ success in subsequent courses? (Fashant et al., 2020) - How will this course provide insights that will enhance students’ professional and personal lives? (Fashant et al., 2020)

A learning outcome is a statement that specifically identifies the knowledge, skills, or attitudes learners should be able to demonstrate after completing a course or a unit of study. Learning outcomes should be measurable and observable, and clearly stated so that students and instructors understand what is expected and will be measured (Fink 2013; Wiggins & McTighe 2005). Moreover, strong learning outcomes are student-centered, specific, and realistic, appropriate to your discipline and course.

Student-centered learning outcomes describe what students will be able to do, using active verbs. For example, “students will be able to apply concept X to topic Y.” Bloom’s taxonomy offers a useful classification of the types of work students can do to demonstrate learning:

Several free online tools available from the University of Ottawa and the University of Central Florida can help you write good, clear, and student-centered learning outcomes that emphasize the purpose and outcomes of the course. Many instructors find GenAI is helpful for turning your goals for the course into clearer and more concise outcomes. Fink (2013) identifies six key areas to consider when developing learning outcomes: foundational knowledge, application, integration, human dimension, caring, and learning how to learn.

Here are some sample learning outcomes from various disciplines:

- Students will explain and evaluate how researchers apply the principles and standards from the APA Ethics Code in the design, data collection, interpretation, and reporting of psychological research. (Psychology)

- Students will create documents that demonstrate an understanding of common technical writing genres. (Technical writing)

- Students will describe and predict basic thermodynamic state functions (∆H, ∆G, ∆S) for chemical reactions. (Chemistry)

- Students will explain the major processes operating in earth science including plate tectonics, waste disposal, the origin of mineral and energy resources. (Earth Sciences)

- Students will develop a defensible holistic novel business approach with the understanding of why this is critical to success in a highly dynamic context. (Entrepreneurship)

Find additional examples here.

- Build the course outline.

- Choose relevant, meaningful, diverse material that reflects your discipline or subject area and fits firmly within the confines of your course as defined by your student learning outcomes. Consider the importance of inclusive and diverse content and strategies for connecting disciplinary excellence to real-world relevance.

- Consider Open Educational Resources. University librarians can help you find these resources, and their OER Guide is very comprehensive.

- Choose relevant, meaningful, diverse material that reflects your discipline or subject area and fits firmly within the confines of your course as defined by your student learning outcomes. Consider the importance of inclusive and diverse content and strategies for connecting disciplinary excellence to real-world relevance.

- Create clear assignments and assessments.

- Plan active teaching and learning activities.

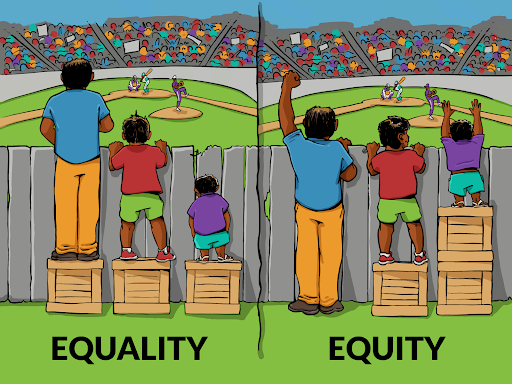

- Review content, assessment, and activities to ensure equitable outcomes.

- Equity-minded instructors continually work to create equitable and inclusive teaching:

- Examine biases: one’s own, one’s discipline’s, the history of education’s.

- Understand learning differences, known and unknown. Implement UDL.

- Address the power of stereotype threat, and use tools to mitigate stereotype threat.

- Use measurement and assessment within the context of bias mitigation.

- Remember the value of diverse representation, references, and examples, both with respect to course materials and guest speakers.

- Ask whether your course cultivates belonging for all learners in the class.

- Consider whether your material, assignments, and activities may or may not be relevant and inviting to the wide range of students who attend Montclair.

- Equity-minded instructors continually work to create equitable and inclusive teaching:

Image from: Interaction Institute for Social Change; Artist: Angus Maguire

- Assess the amount work you are assigning students: is it reasonable and manageable? Wake Forest University has developed a workload estimator tool that might be useful.

Meaningful Redesign for Troublesome Moments in Teaching: Conference Archive (2022).

Fashant, Z., Russell, L., Ross, S., Jacobson, J., LaPlant, K. P., Hutchinson, S., & Fink, L. D. (2020). Designing effective teaching and significant learning. Stylus.

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences : an integrated approach to designing college courses (Revised and updated edition. Jossey-Bass

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (Expanded 2nd). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

For more information or help, please email the Office for Faculty Excellence or make an appointment with a consultant.

Last Modified: Wednesday, January 8, 2025 11:19 am

VS![]()

Teaching Resources by Montclair State University Office for Faculty Excellence is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

Third-party content is not covered under the Creative Commons license and may be subject to additional intellectual property notices, information, or restrictions. You are solely responsible for obtaining permission to use third party content or determining whether your use is fair use and for responding to any claims that may arise.