Creativity and Bridging – by Philip Barnard and Scott deLahunta

Posted in: Guest Essay

“Abstract art is only painting. And what’s so dramatic about that? There is no abstract art. One must always begin with something. Afterwards one can remove all semblance of reality; there is no longer any danger as the idea of the object has left an indelible imprint. It is the object which aroused the artist, stimulated his ideas and set off his emotions. These ideas and emotions will be imprisoned in his work for good… Whether he wants it or not, man is the instrument of nature; she imposes on him character and appearance. In my paintings of Dinard, as in my paintings of Purville, I have given expression to more or less the same vision… You cannot go against nature. She is stronger than the strongest of men. We can permit ourselves some liberties, but in details only.”– Pablo Picasso, at Boisgeloup, winter 1934, in Letters of the great artists: from Blake to Pollock, by Richard Friedenthal. London: Thames and Hudson, 1963, pp. 256-257 (translation Daphne Woodward)

This quote from Picasso is rich in latent meaning, not only about the content of multimodal imagery underlying artistic endeavour, but also concerning the way in which ideas are translated from sources of inspiration (“One must always begin with something…”) to an artistic product (“[his] paintings of Dinard and Pourville”) and how it is to be interpreted in the broader social context of artistic practice.

The statement, in and of itself, is silent about the means — both mental and physical — through which creativity is realised. The nature of creative endeavour, be it in fine art, graphic design, choreography or even science, involves bridging between the sources of inspiration that drive a form of enquiry and its outcomes.

As a part of a project exploring creativity in dance, Wayne McGregor | Random Dance have been researching rich ways of describing and unpacking creative practices with a view to augmenting them. A key element of this research recognises that we just don’t get from an “idea” to an artistic outcome in a single leap; the process involves bridging, in which mental processes, discovery representations and production representations all play crucial parts.

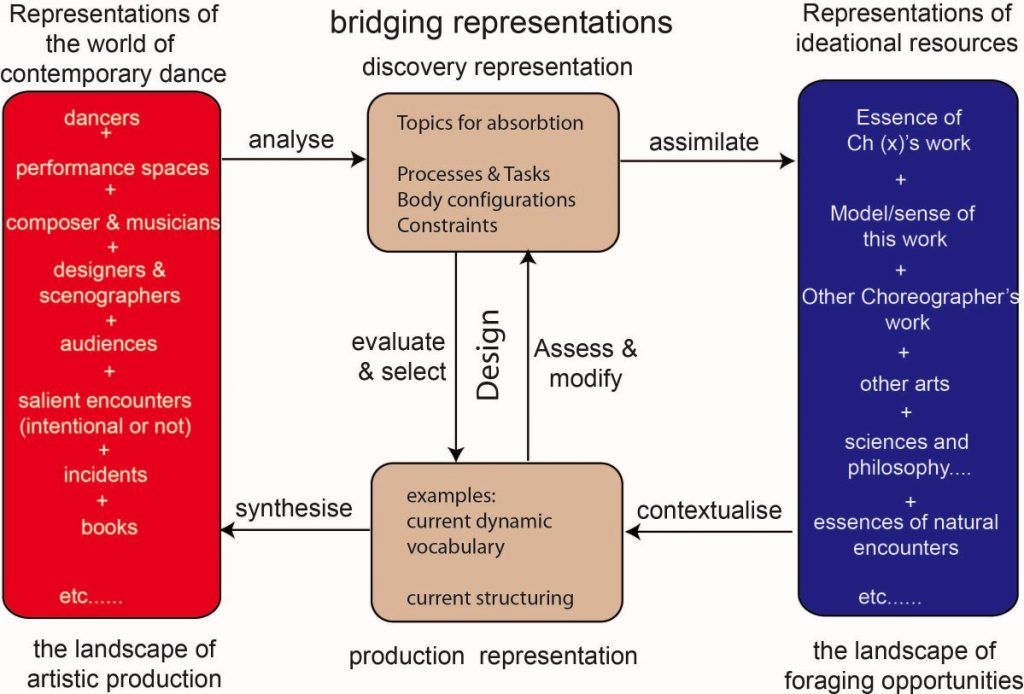

The bigger picture we envision for supporting discussion of what we have in mind is shown in our model of what is involved in bridging between sources of inspiration and artwork that appears in its social context. Here we focus specifically on choreography; however, this form of “model” can, in principle, be applied to any design practice, such as technology design (Barnard, 1991) or the design and development of diagnostic tests and therapeutic interventions for mental illness (Barnard, 2004).

The diagram is composed of boxes that contain “stuff” or representations; and arrows that are labelled as specific processes (analyse, assimilate, evaluate and select, assess and modify, contextualise, and synthesise).

On the left hand side of the diagram is a box labelled “representations of the world of contemporary dance” – or, more widely, any other landscape of artistic production. We can easily know a great deal about what is “out there” in the world of contemporary dance with the constraints provided by specific dancers, performance spaces, audiences, DVDs of productions and so on.

On the right hand side of the diagram we can also say something about the “representations of ideational resources” that an artist reports drawing upon – from books, poetry, senses of meaning in the essence of their own work as well as that of others, images, or even the meanings that come out of natural encounters with people, places or events.

Wayne McGregor, like many other artists, forages voraciously through such sources.

Crucially, in the centre of the diagram are two further boxes labelled “discovery representation” and “production representation”. These are called into play at the time of making an artwork. In the case of Wayne McGregor | Random Dance, McGregor himself will have number of topics in mind that he is quite explicitly using to generate the imagery for the processes and tasks (discovery representations) he uses in making. The classes of processes that he uses to arrive at a particular movement vocabulary are also readily open to description – and, indeed, such descriptions are available (Kirsh et al., 2009).

Equally, at any point in the evolving process of creation, production representations in one form or another (e.g. videos, notebooks, diagrams, emails) can capture the current state of the production (ultimately, of course, in other domains there might be scores, storyboards or scripts, etc.).

The “easy” part in many respects of exposing design work is characterising the representations involved. Here we have much to work with in terms of artefacts, documents and even interviews with, or writings of, the artists themselves.

The hard part is characterising the processes – the arrows that link the boxes. These are processes that go on in the minds of the practitioners. In the context of Wayne McGregor | Random Dance, these include dancers, choreographers, scenographers, lighting designers, and costume designers.

It is in the collective mental processes of analysis, assimilation, evaluation and selection, assessing and modifying, contextualising and synthesizing that the real magic of creativity lies. That magic is not some un-analysable mass. It involves deep expertise, large numbers of small steps and many, many individual decisions.

The diagram’s decomposition of what might be involved is not intended to reduce creativity to some simple-minded elements, but rather to provide a rich way of indexing the real intricacies of creativity in action. In this way, we hope to provide platforms for debate, exploration and augmentation of artistic practice. To do this, we draw on other and more detailed, models of the processes involved in choreographic practice and models derived from cognitive neuroscience of the human mind.

We do not expect to unravel all the secrets of creativity, but just enough to provide practical insights to stimulate the minds of practitioners in how to evolve and enhance their own practices; and, in pedagogy, to excite and stimulate the minds of new generations of artists by providing them with ways of seeing more clearly how the elements of creative skills are realised and how they could undergo systematic development in the future.

— Philip Barnard, MRC Cognition & Brain Sciences Unit, Cambridge; and Scott deLahunta, R-Research Wayne McGregor | Random Dance, Sadler’s Wells, London.

Sources cited

Barnard, P. J. (1991). Basic theories and the artefacts of HCI. In J. M. Carroll (Ed.), Designing interaction (pp. 103–127). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Barnard, P.J. (2004). Bridging between basic theory and clinical practice. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 42, 977–1000.

Kirsh, D. et al., (2009). Choreographic methods for creating novel, high quality dance. In: Proceedings of the 29th Annual Conference of the Design and Semantics of Form and Movement (pp. 188-195). Lucerne, Switzerland: Design and Semantics of Form and Movement.