Programs for the Preparation of Educators

The conceptual framework that guides programs for the preparation of educators at Montclair State University is grounded in a vision of schooling in a democratic society. Our explicit emphasis on the interconnection of education and democracy grew out of our participation in the National Network for Educational Renewal (NNER) and the Agenda for Education in a Democracy (AED), both based on the work of John Goodlad. Consistent with the conceptual underpinnings of the NNER and AED, Montclair State’s programs for teachers and other school professionals emphasize the moral dimensions of schooling in a democracy and promote a view of educators as ethical decision-makers responsible for disrupting inequities in school and assuring the engagement and learning of all students. Such work demands a commitment to civic responsibility and to critically examining the nature, causes and means for eradicating social and institutional inequalities as well as to fostering the development of best practices for supporting productive learning for all students.

In keeping with the NNER goals, our programs for educators are guided by four principles:

- Providing access to knowledge for all children and youth;

- Forging caring and effective connections with all children and youth;

- Fostering in the young the skills, dispositions and knowledge necessary for effective participation in a social and political democracy; and

- Ensuring responsible stewardship and change agency in schools.

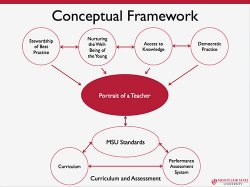

The diagram below provides a visual representation of the Montclair State University Conceptual Framework and its relationship to our Standards, Curriculum and Assessment System.

Below we provide a brief explanation of each of the four guiding principles.

Providing access to knowledge for all children and youth

Central to our conceptual framework is the belief that a purpose of schools in democratic societies is to give all children and youth access to knowledge. In a post-industrial world, that means enabling P-12 students to attain academic standards that are considerably higher than basic literacy and numeracy. Today’s students need a deeper knowledge of content than that promoted by the traditional transmission approach to teaching. They also need to develop critical thinking skills—the ability, for example, to analyze and synthesize disparate information, to make reasoned judgments based on sound criteria, and to apply information and judgments to real-world situations in order to solve problems. Students in elementary and secondary schools must also develop facility with new technologies. Without access to these types of knowledge, young people will be unable to become active participants in a democratic society.

It is well documented, however, that all children do not have equal access to learning. Students in poor schools and communities, for example, tend to have less access to educational resources, including well-prepared teachers, than children in more affluent schools and communities. Even when the curriculum is very similar, teacher expectations and other factors lead to different outcomes in different types of schools. Specifically, children who attend schools in low income communities and who are of racial/ethnic minority backgrounds tend to do less well academically than their more affluent white peers. Since access to knowledge is access to power, offering vastly different educational resources and experiences to different groups of students is morally unacceptable. We at Montclair State are committed to preparing educators who will take a stand against inequitable school practices and are able to enact an unrelenting focus on student learning and engagement. This does not mean rote “teaching to the test;” instead it means setting student learning goals for deep understanding of relevant and challenging curricula for all students and using valid assessments to measure that learning and inform ongoing instruction.

Forging caring and effective connections with all children and youth

Our commitment to preparing teachers and other school professionals who build caring and effective connections with all young people is another principle that informs programs for educators at Montclair State University. The educators we aim to prepare not only to hold themselves to a high standard for ensuring that all children develop subject matter knowledge, critical thinking skills, and technological abilities, but also attend to the relationships inherent in schooling. Such educators engage students as multi-dimensional and multi-talented persons, helping them develop cognitively, socially and affectively. Helping students develop the skills and dispositions to think critically as one aspect of nurturing pedagogy. We view nurturing pedagogy as being based on knowledge of subject matter, students, families, communities and curriculum goals and standards; and as taking into account issues of class, gender, race, ethnicity, language, sexual orientation, age and special needs.

Fostering in the young the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary for effective participation in a social and political democracy.

The third principle that informs our work is the belief that schools and educators are responsible for fostering in the young the knowledge, skills and dispositions to participate in a social and political democracy. Education and democracy are inextricably linked; the maintenance of democracy depends on having an educated populace to make decisions for the common good. Schooling is the only social institution responsible for developing in young people the abilities and dispositions to become active and engaged members of a democracy. To us at Montclair State, this means schools must ensure that all children learn to think well (i.e., critically) in the context of a community, learn to value different points of view and feel responsible for the well-being of the community.

Ensuring responsible stewardship and change agency in schools

The fourth principle that grounds the preparation of educators at Montclair State University is the conviction that teachers and other school professionals need to see themselves as stewards of best practice and agents of change in classrooms and schools. We want to prepare educators who feel responsible for ensuring that schools educate all students, who see themselves as moral actors, and who will take a stand against mediocrity and inequity. Such educators recognize that teaching is a complex activity that is inherently political and ethical. They are aware that institutional structures and practices do not exist in a vacuum, but that people build and sustain them, whether consciously or unconsciously. They understand that, while education has the potential to challenge and transform inequities in society, without intervention, schools tend to reproduce those inequities by giving greater status to the ways of thinking, talking and behaving of the dominant cultural group. They do not see themselves as technicians but as inquiry-oriented decision makers. While it is a tall order to prepare such educators because so many policies and practices in schools work against them, we are nevertheless committed to doing so.

The centerpiece of the Unit’s conceptual framework is The Portrait of a Teacher, which grew out of the four principles above and which reflect the InTASC Standards. Developed by faculty from the Unit and partner schools, the Portrait is a set of statements that translate the philosophical principles we embrace into a tangible vision of the teacher in a democratic, multicultural society. Originally developed in 1994, the document was revised in 1999 and 2003. While the Portrait focuses specifically on the teacher, the vision it articulates serves as a common foundation for all Unit programs. (The Portrait is accessible on the Center of Pedagogy website: Center of Pedagogy.) Below, we highlight the salient characteristics of the teacher/educator depicted in the Portrait.

The socially and culturally responsive educators we aim to produce:

- 1. Know the subject matter they teach/the knowledge base of the professional field they practice

- There is general agreement in the teacher education literature that “knowledge of the content to be taught underlies all aspects of good instruction” (Dwyer, 1994, p. 23). To give their students access to knowledge, teachers need to understand the concepts, structures, purposes and processes of inquiry in the disciplines they teach. They need a grasp of the subtleties, contradictions and unanswered questions in their disciplines as well as the uncontested knowledge. That is, they need a “flexible” understanding of subject matter to be able to adapt it to different learners (McDiarmid, Ball, & Anderson, 1989). In addition, they need to understand and be able to use appropriate content-specific pedagogical practices (Ball & Forzani, 2009). School professionals other than teachers also must develop an in-depth understanding of the professional knowledge base in their fields. While the details of this knowledge base vary according to the roles such professionals play in schools, it includes an understanding of learning and how it develops in various school, family and community contexts; the appropriate uses of various forms of student assessment and of technology; professional ethics, law and policy; the nature and appropriate uses of research and other data to improve student learning; and how they can promote student learning.

- 2. Understand how children and adolescents learn in a variety of contexts

- To promote learning on the part of children and youth, teachers and other school personnel must understand the learning process. Cognitive science tells us that learning is a process by which learners generate meaning in response to new ideas and experiences they encounter, by using their prior knowledge and beliefs to make sense of new input (Glasersfeld, 1995; Piaget, 1977). Thus, the knowledge children bring to school, derived from personal and cultural experiences, is central to their learning. Learning involves both an intrapersonal dimension and an interpersonal, or social, dimension (Bruner, 1966, 1996; Cole, 1996; Vygotsky, 1978). That is, learners use their prior knowledge and beliefs to make sense of new input. At the same time, learning is situated within a sociocultural context and social relationships are essential to learning. Ultimately, it is an understanding of student learning that must orient educators’ practice.

- 3. Are culturally responsive.

- In our increasingly diverse society, teachers and other school professionals must be responsive to both the individual and cultural backgrounds of the students in their care (Banks et al., 2005; Ladson-Billings, 2009; Nieto, 2005). Our conception of the culturally responsive educator encompasses six salient characteristics adapted from the work of Villegas and Lucas (2002a, 2002b). Such educators: (1) are socioculturally conscious—that is, they recognize that there are multiple ways of perceiving reality and that these ways are influenced by one’s position in the social order; (2) have affirming views of students from diverse backgrounds and see their differences as resources for learning, not problems to be remedied; (3) see themselves as both responsible for and capable of bringing about educational change that will make schools more responsive to all students; (4) understand how learners construct knowledge and are capable of promoting learners’ knowledge construction in the various capacities they interact with students; (5) know about the lives of the students they serve in order to help them build bridges to learning; and (6) use their knowledge about students’ lives to help them achieve high academic standards. We consider these qualities essential for educators in our increasingly multicultural society.

- 4. Plan their practice based upon knowledge of the subject matter, students and their families/communities, and curriculum goals and standards.

- Teachers need to be able to plan instruction based on their knowledge of subject matter, their understanding of the curriculum goals and standards and their insight into students’ lives. Instruction and other educational services must be designed to take into account the diversity among students related to such factors as class, gender, race, ethnicity, language, sexual orientation, age and special needs. Teachers who take these factors into account plan instruction that uses pertinent examples and analogies from learners’ lives to introduce or clarify new concepts (Banks, 1996; Irvine, 1992); draw on the expertise of parents and community members; incorporate into their teaching cultural patterns from children’s home and community experiences; draw on students’ linguistic resources, including their home language (Garcia, Kleifgen, & Flachi, 2008; Lucas & Villegas, 2011); and help students interrogate the curriculum critically by having them address inaccuracies and omissions (Banks, 1991, 1996; Cochran-Smith, 1997; Cochran-Smith, 2010).

- 5. Understand critical thinking and problem solving, and create and support learning experiences that promote the development of these skills and dispositions.

- Our view of critical thinking grew out of the work of Matthew Lipman, a Montclair State University scholar, who defines critical thinking as reflective thought involving the making of judgments that rely on criteria, are sensitive to context, are self-correcting and occur within a community of inquiry (Lipman 1988; Lipman, Sharp & Oscanyan, 1980). Critical thinking, constructivist views of learning and teaching, and democratic practice go hand in hand. By emphasizing authentic conversations about meaningful problems, constructivist classrooms promote critical thinking and sensitivity to context, the recognition of multiple perspectives and collaboration (Villegas & Lucas, 2002a)—all features of critical thinking. Similarly, all participants in a democracy must be able to think critically so they can make positive contributions to the society (Soder, 1996).

- 6. Understand principles of democracy and model democratic values and communication in classrooms and schools.

- To promote the values of social justice and diversity inherent in a democratic society, educators need to understand the concept of democracy and possess the ability to model democratic practices. For purposes of education, it is important to make the distinction between a political democracy and a social democracy (Goodlad, 1997). In Dewey’s conception, democracy is “more than a form of government;” it is “primarily a mode of associated living” (1966, p. 87). The relationships between educators and students are central to this vision as well (Arum, 2011). It is the responsibility of schools not only to teach young people about democratic political governance, but also to foster “the democratic way of life” (Beane and Apple, 1995, p. 6). Among the conditions Beane and Apple identify as necessary for the latter are the open flow of ideas; faith that individually and collectively people can create solutions to problems; critical reflection and analysis of ideas, problems, and policies; concern for the welfare of others; concern for the dignity and rights of individuals and minorities; and the organization of social institutions to promote the democratic way of life. We seek to prepare educators who embrace these conditions inside and outside schools.

- 7. Understand and use multiple forms of assessment to promote the development of learners and to inform their practice.

- If the goal of schools is to educate all students to high levels of achievement—as we believe it should be—then assessments must be used in the service of improving teaching and learning. Assessment should be used to help educators identify the strengths and needs of students so they can determine the most effective ways of building on what children already know to help them grow academically (Pellegrino, Chudowsky, & Glaser, 2001). Students need a variety of routes to demonstrate their knowledge (Cochran-Smith, 1999; Oakes & Lipton, 1999; Villegas, 1991; Zeichner, 1992) because reliance on a single type of assessment task creates disadvantages for some learners. Educators should have knowledge of different classroom assessments and the skill to use assessment data to inform instruction (Bettesworth, Alonzo, Duesbery, 2009). They should also understand technical issues related to classroom assessments and standardized tests and recognize the appropriate uses as well as limitations of standardized tests (Popham, 2001). Consistent with the goals of the Partnership for 21st Century Skills, educators need to be able to design and/or select authentic tasks that give insight into students’ thinking, develop high-order cognitive skills, and promote life-long learning (Nicaise, Gibney, & Crane, 2000). In sum, teachers need to teach in ways that foster the reciprocal integration of standards, curriculum, assessment and instruction (Castellain & Carran, 2009).

- 8. Create school and classroom communities that are nurturing, caring, safe, and conducive for learning.

- The way schools and classrooms are organized and the resulting relationships between teachers and students have profound implications for students’ learning. To be nurturing, caring, safe and conducive to learning, classroom communities need to foster rapport between educators and students, help learners believe they can succeed, and establish and maintain fair and constructive standards of behavior (Dwyer, 1994; Noddings, 2005). They also need to engage all students—not just the most advanced—“actively in purposeful, meaningful, collaborative, intellectually rigorous, and language-rich activities” (Villegas & Lucas, 2002a, p. 95), build on students’ strengths, and ensure that all students know the culturally and linguistically appropriate ways of participating in the classroom (Valdés, Bunch, Snow, & Lee, 2005; Villegas, 1991).

- 9. Are reflective practitioners who continually engage in inquiry and seek out opportunities that promote their professional growth.

- Reflection is essential to becoming the type of educator we seek to prepare (see Dewey, 1933; Louden, 1991; Schön, 1983; Zeichner, 1992, 1996). In a preservice teacher preparation program, we can only prepare excellent beginning teachers. To continue to develop expertise throughout a career, educators must engage in purposeful and reflective learning about teaching, learning and students (Feiman-Nemser, 2001; Lampert, 2010). Educators who ask themselves questions about their own practice and who seek to understand the influences of the social, political and cultural context must gather information in systematic ways to answer their questions and must seek opportunities to become more knowledgeable and skilled professionals. (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009; Maloney, Moore, &Taylor, 2011) Reflection in and of itself, however, does not necessarily result in better teaching or more equitable school practices. Zeichner (1996) delineates three characteristics of reflective practice that promote social justice and equity: the teacher focuses attention both inwardly toward her own practice and outwardly toward the social context for the practice; reflection focuses on social and political dimensions of schooling; and the educator is committed to reflection as social practice, not simply introspection on apparently neutral professional practices. Our perspective on teacher reflection is consistent with this view.

- 10. Are skilled at building relationships with school colleagues, students’ families, and community agencies to support students’ learning and well-being.

- When educators work in partnerships with colleagues, parents/guardians, and community members, they increase the resources available for student learning and maximize students’ academic growth (Arvizu, 1996; Jeynes, 2011; Ross & Regan, 1993). In their relationships with colleagues, educators need to know from whom they can seek help, who might need their help, and with whom they might want to collaborate (Dwyer, 1994). The importance of teachers’ building relationships with parents to support their involvement in their children’s education is widely recognized (see Arvizu, 1996; Bempechat, 1990; Cruikshank, 1990; Gimbert, Desai,& Kerka, 2010; Jeynes, 2011; Nieto, 1996). Similarly, collaborations between schools and community members can contribute significantly to student success (Lucas, 1997).

- 11. Speak and write English fluently and communicate clearly.

- Teachers teach communication skills to their students; both teachers and other school professionals must model appropriate communication skills for P-12 student. Therefore, it is essential that educators be fluent in spoken and written English communication skills.

- 12. Model dispositions that are consistent with ethical decision-making and stewards of best practice.

- Most of the above eleven qualities we seek to foster through our programs for educators can be characterized as knowledge and skills. Underlying them is a set of dispositions we expect of candidates enrolled in preparation programs for teachers and other school personnel at Montclair State. For us, dispositions encompass attitudes, commitments, beliefs, and values (Feiman-Nemser & Remilard, 1996; Freeman, 2007; Richardson, 1996; Sockett, 2008; Villegas, 2007). These dispositions are critical to the vision of the responsive educator described above. The educators we aim to produce: believe in the educability of all children; respect each individual and cultural group; believe that all children bring talents and strengths to learning; see students’ strengths as a basis for growth and their errors as opportunities for learning; are committed to using assessment to identify students’ strengths and promote students’ growth rather than to deny students access to learning opportunities; appreciate multiple perspectives on knowledge; are committed to the expression and use of democratic values in the schools; are committed to critical reflection, inquiry, critical thinking, and life-long learning; are committed to the ethical and enculturating responsibilities of educators; and believe in the potential of schools to promote social justice, and to being agents of change and stewards of best practice.

References

Arum, R. (2011). Reformers have ignored one factor that could propel student learning: Restoring moral authority to relationships between students and educators. Phi Delta Kappan, 93(2), 9-13.

Arvizu, S. F. (1996). Family, community, and school collaboration. In J. Sikula (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education (2nd Ed.), pp. 814-819.

Ball, D. L., & Forzani, F. M. (2009). The work of teaching and the challenge of teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(5), 497-511.

Banks, J. (1991). A curriculum for empowerment, action, and change. In C. E. Sleeter (Ed.), Empowerment through multicultural education, pp. 125-141. Albany: SUNY Press.

Banks, J. (1996). The historical reconstruction of knowledge about race: Implications for transformative teaching. In J. A. Banks (Ed.), Multicultural education, transformative knowledge, and action: Historical and contemporary perspectives, pp. 64-87. NY: Teachers College Press.

Banks, J., Cochran-Smith, M., Moll, L., Richert, A., Zeichner, K., LePage, P…., McDonald, M. (2005). Teaching diverse learners. In L. Darling-Hammond & J. Bransford (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 232-274). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Barber, B. R. (1997). Public school: Education for democracy. In J. I. Goodlad & T. J. McMannon (Eds.), The public purposes of education and schooling, pp. 21-32.

Beane, J. A., & Apple, M. W. (1995). Democratic schools. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Bempechat, J. (1990). The role of parent involvement in children’s academic achievement: A review of the literature. NY: ERIC Clearinghouse on Urban Education.

Bettesworth, L. R., Alonzo, J., Duesbery, L. (2009). Swimming in the depths: Educators’ ongoing effective use of data to guide decision making. In T. J. Kowalski & T. J. Lasley II (Eds). Handbook of Data Based Decision Making in Education.(pp. 286-303). New York: Routledge.

Bruner, J. (1966). Toward a theory of instruction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Castellain, J. & Carran, D. (2009). Creative decision-making strategies through technology-based curriculum tools. In T. J. Kowalski & T. J. Lasley II (Eds). Handbook of Data Based Decision Making in Education. (pp. 304-316). New York: Routledge.

Cochran-Smith, M. (1997). Knowledge, skills, and experiences for teaching culturally diverse learners: A perspective for practicing teachers. In. J. J. Irvine (Ed.), Critical knowledge for diverse teachers and learners, pp. 27-87. Washington, D.C.: American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education.

Cochran-Smith, M. (1999). Learning to teach for social justice. In G. Griffin (Ed.), The education of teachers. Ninety-eighth Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education, pp. 114-144. Chicago: National Society for the Study of Education.

Cochran-Smith, M. (2010). Toward a theory of teacher education for social justice. In M. Fullan, A. Hargreaves, D. Hopkins, & A. Lieberman (Eds.), The international handbook of educational changes (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2009). Inquiry as stance: Practitioner research in the next generation. New York: Teachers College Press.

Cole, M. (1996). Cultural psychology: A once and future discipline. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cruickshank, D. R. (1990). Research that informs teachers and teacher educators. Bloomington, IN: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation.

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think. Lexington, MA: Heath.

Dewey, J. (1966). Democracy and education. New York: Free Press. (Original work published 1916).

Dwyer, C. A. (1994). Development of the knowledge base for the Praxis III: Classroom Performance Assessments Assessment Criteria. Princeton, NJ: ETS.

Feiman-Nemser, S., & Remillard, J. (1996). Perspectives on learning to teach. In F. B. Murray (Ed.), The teacher educator’s handbook: Building a knowledge base for the preparation of teachers, pp. 63-91. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Feiman-Nemser, S. (2001). From preparation to practice: Designing a continuum to strengthen and sustain teaching. Teachers College Record, 103(6), 1013-1055.

Freeman, L. (2007). An overview of dispositions in teacher education. In M. E. Diez & J. Raths (Eds.), Dispositions in teacher education (pp. 3-29). Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

García, O., Kleifgen, J. A., & Falchi, L. (2008). From English language learners to emergent bilinguals. Equity Matters: Research Review No. 1. New York: Campaign for Educational Equity, Teachers College, Columbia University.

Gimbert, B., Desai, S., & Kerka, S. (2010). The big picture: Focusing urban teacher education on the community. Phi Delta Kappan, 92(2), 36-39.

Glasersfeld, E. von. (1995). Radical constructivism: A way of knowing and learning. London: The Falmer Press.

Goodlad, J. I. (1994). Educational renewal: Better teachers, better schools. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Goodlad, J. I. (1997). In praise of education. NY: Teachers College Press.

Goodwin, A. L. (1997). Introduction. In A. L. Goodwin (Ed.), Assessment for equity and inclusion: Embracing all our children, pp. xiii-xvi. NY: Routledge.

Goodwin, A. L., & Macdonald, M. B. (1997). Educating the rainbow: Authentic assessment and authentic practice for diverse classrooms. In A. L. Goodwin (Ed.), Assessment for equity and inclusion: Embracing all our children, pp. 229-240. New York: Routledge.

Irvine, J. J. (1992). Making teacher education culturally responsive. In M. E. Dilworth (Ed.), Diversity in teacher education: New expectations, pp. 79-92. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Jeynes, W. (2011). Help families by fostering parental involvement. Phi Delta Kappan, 93(3), 38-39.

Labaree, D. F. (1997). Public goods, private goods: The American struggle over educational goals. American Educational Research Journal, 34(1): 39-81.

Ladson-Billings, G. (2009). Race still matters: Critical race theory in education. In M. Apple, W. Au, & L. A. Gandin (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of critical education (pp. 110-122). New York and London: Routledge.

Lampert, M. (2010). Learning teaching in, from, and for practice: What do we mean? Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1-2), 21-34.

Lee, J. (2002). Racial and ethnic achievement gap trends: Reversing the progress toward equity? Educational Researcher, 31(1), 3-12.

Louden, W. (1991). Understanding teaching: Continuity and change in teachers’ knowledge. NY: Teachers College Press.

Lipman, M. (1988). Philosophy goes to school. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Lipman, M., Sharp, A. M., & Oscanyan, F. (1980). Philosophy in the classroom. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Lucas, T. (1997). Into, through, and beyond secondary school: Critical transitions for immigrant youths. Washington, D.C. & McHenry, IL: Center for Applied Linguistics and Delta Systems.

Lucas, T., & Villegas, A. M. (2011). A framework for preparing linguistically responsive teachers. In T. Lucas (Ed.), Teacher preparation for linguistically diverse classrooms: A resource for teacher educators (pp. 55-72). New York: Routledge.

Maloney, D., Moore, T., & Taylor, M. (2011). Grassroots growth: The evolution of a teacher study group. Learning Forwards Journal, 32(5), 46-49.

McDiarmid, G. W., Ball, D. L., & Anderson, C. R. (1989). Why staying one chapter ahead doesn’t really work: Subject-specific pedagogy. In M. C. Reynolds (Ed.), Knowledge base for the beginning teacher. NY: Pergamon Press.

Nicaise, M., Gibney, T. & Crane, M. (2000). Toward an understanding of authentic learning. Student perception of an authentic classroom. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 9, 79-94.

Nieto, S. (1996). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context of education. White Plains, New York: Longman.

Nieto, S. (2005).

Noddings, N. (1984). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Noddings, N. (2005). The challenge to care in schools: An alternative approach to education (2nd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press.

Oakes, J., & Lipton, M. (1994). Tracking and ability grouping: A structural barrier to access and achievement. In J. Goodlad and P. Keating (Eds.), Access to knowledge: The continuing agenda for our nation=s schools, pp. 187-204. NY: The College Board.

Pellegrino, J. W., Chudowsky, N., & Glaser, R. (2001). Knowing What Students Know: The science and design of educational assessment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Piaget, J. (1977). The development of thought: Equilibrium of cognitive structures. Translated by A. Rosin. New York: Viking Press.

Popham, J.W. (2001). The truth about testing: An educator’s call to action. Alexandria, VA: ASCD

Richardson, V. (1996). The role of attitudes and beliefs in learning to teach. In J. Sikula (Ed.), Handbook of research on teacher education, 2nd Edition, pp. 102-119. New York: Macmillan.

Ross, J. A., & Regan, E. M. (1993). Sharing professional experience: Its impact on professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 9(1), 91-106.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner. NY: Basic Books.

Sockett, H. (2008). The moral and epistemic purposes of teacher education. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, & K. E. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 45-65). New York: Routledge.

Soder, R. (1996). Teaching the teachers of the people. In R. Soder (Ed.), Democracy, education and the schools, p. 246. San Francisco: Jossey Bass.

Stanton-Salazar, R. D. (2001). Manufacturing hope and despair: The school and kin support networks of U.S.-Mexican youth. NY: Teachers College Press.

Tom, A. R. (1997). Redesigning teacher education. Albany: SUNY Press.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2002). The condition of education 2002, NCES 2002-025. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. (2003). The condition of education 2003, NCES 2003-067. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Valdés, G., Bunch, G., Snow, C., & Lee, C., with Matos, L. (2005). Enhancing the development of students’ language(s). In L. Darling-Hammond & J. Bransford (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 126-168). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Villegas, A. M. (1991). Culturally responsive teaching for the 1990s and beyond. Washington, D.C.: American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education.

Villegas, A.M., & Lucas, T. (2002a). Educating culturally responsive teachers: A conceptually coherent and structurally integrated approach. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Villegas, A.M., & Lucas, T. (2002b). Preparing Culturally Responsive Teachers: Rethinking the Curriculum. Journal of Teacher Education, 53, no. 1, pp. 20-32.

Villegas, A.M. (2007). Dispositions in teacher education: A look at social justice. Journal of Teacher Education, 58(5), 370-380.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Zeichner, K. (1992). NCRTL special report: Educating teachers for cultural diversity. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University, National Center for Research on Teacher Learning.

Zeichner, K. (1996). Designing educative practicum experiences for prospective teachers. In K. Zeichner, S. Melnick, and M. L. Gomez (Eds.), Currents of reform in preservice teacher education, pp. 199-214. New York: Teachers College Press.

(rev. January 2012)